YOUR FITNESS BLOG

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis For Weight Loss

In a previous article, we explained that weight regain largely occurs because of a reduction in spontaneous physical activity referred to as non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). Moreover, NEAT appears to play a critical role in overweight and obese individuals as these populations consistency demonstrate reduced standing and walking time [2]. Because NEAT encompasses such a wide variety of activity, it is considered the most variable component of total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) ranging from 15% in sedentary people to 50% or more of TDEE in highly active individuals [3].

What is Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT)?

NEAT refers to all forms of physical activity that are non-volitional or spontaneous in nature [1]. For example, NEAT includes energy expended from occupation, sitting, standing, walking, and toe-tapping [2]. It does not include purposeful or structured physical activity (i.e. resistance exercise, cycling, running, personal training sessions).

How is NEAT Measured?

There are two primary methods to measure NEAT [3]:

- Estimate NEAT direct by calculating total daily energy expenditure (TDEE), then subtracting basal metabolic rate (BMR) and thermic effect of food (TEF)

2. A factoral approach that uses a diary log of physical activity over a given period (e.g. 7 days).

In the research, TDEE is typically measured using a room calorimeter whereby gas exchange and heat loss are measured in a confined chamber [3]. An alternative method, with a high degree of accuracy, involves using double labelled water to estimate carbon dioxide production and energy expenditure [3]. For the purpose of this article, a more practical approach to each method is provided below:

1) Estimating NEAT

i. Calculating Total Daily Energy Expenditure

Alan Aragon offers the following equation to estimate TDEE, which accounts for gender and differences in general activity levels [5]:

TDEE = Target bodyweight in kilograms x ((8-10 or 9-11 + average total weekly training hours) * 2.2)

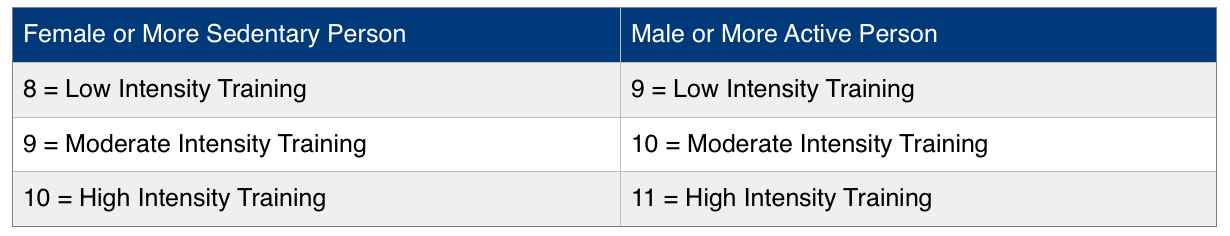

A woman or individual with a more sedentary lifestyle would use the 8-10 range, whereas a man or someone with a more active lifestyle would use the 9-11 range. Intensity of daily exercise and movement is described by the following [5]:

For example, a female with a target bodyweight of 65kg that formally exercises for 2 hours/week at moderate intensity would have a TDEE of 1,573 daily calories (TDEE = 65 x ((9 + 2) * 2.2) = 1,573 daily).

ii. Calculating Basal Metabolic Rate

For both men and women, the following formula offered by Aragon can be used to calculate BMR [5]:

25.3 x Lean Body Mass in Kg

iii. Calculating Thermic Effect of Food (TEF)

TEF represents approximately 10% of TDEE, therefore numerically, this figure is small and often disregarded [1]. However, the formula below can be used to provide an estimate of TEF [1]:

TEF = TDEE x 0.10

2) Factoral Approach

A factoral approach to calculating NEAT tracks physical activity over a given period then identifies the energy equivalent of each activity [3]. To provide an estimate of NEAT, the energy equivalent of each activity is then multiplied by the time spent performing each activity [3]. Instrumentation like pedometers (e.g. Fitbit) or accelerometers, are more practical, everyday methods for quantifying human activity. However, pedometers and are found to be poor predictors of NEAT and useful only for qualifying walking (e.g. steps) [3]. Accelerometers detect body displacement and have the potential to read displacement over multiple angles [3]. Although more precise than pedometers, accelerometers still do not provide a truly accurate assessment of NEAT [3].

Differences in NEAT

Variance in Occupation

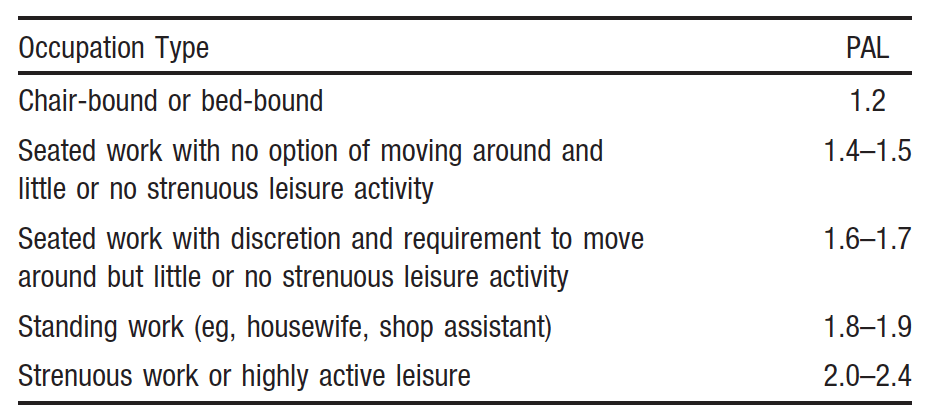

The scientific literature shows that non-exercise activity thermogenesis can vary significantly between individuals by up to 2000 calories per day [1]. The greatest variance in NEAT is associated with differences in occupation [1]. For example, the difference in NEAT between an office worker and labourer may be severalfold [2, 1]. Data for NEAT are often expressed in terms of physical activity level (PAL), which is calculated by dividing TDEE by BMR [2].

Variance in Leisure Activities

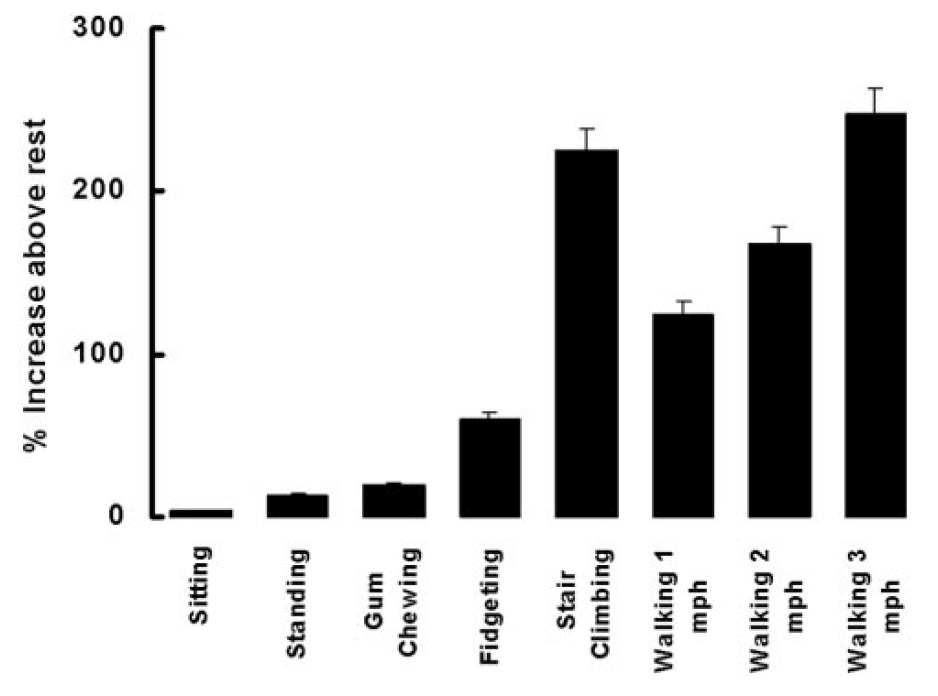

Evidence suggests that differences in leisure activities can vary greatly, thus influencing total daily NEAT [1, 2]. For example, sitting on the sofa watching television after work for 4 hours would represent an energy expenditure of approximately 8% above BMR [1]. If BMR were 1500 kcal/day, this individual would expend about 20 calories for this particular activity (0.08 x 1500 (BMR) x (4 / 24) Hours = 20 kcal).

NEAT In Weight Gain and Re-Gain

Given that energy expenditure directly impacts weight loss or gain, it is understandable that reduced NEAT could result in weight gain via decreased energy output. In fact, there is substantial evidence showing that overweight and obese individuals maintain lower NEAT levels compared to lean individuals [2, 7]

To illustrate the impact of NEAT on weight gain, Levine and colleagues (1999) showed that changes in spontaneous activity accounted for a 10-fold difference in fat storage among subjects [4]. In their study, the authors overfed 16 non-obese subjects 1,000 calories per day above maintenance calorie level [4]. Over a 8-week study period, fat gain varied substantially from 0.36kg to 4.23kg and was inversely related to increases in daily energy expenditure [4].

The authors found only marginal increases in basal metabolic rate (5%) and thermic effect of food (14%) [4]. However, average daily NEAT increased by 336 kcal/day, which accounted for two-thirds of the increase in daily energy expenditure [4]. Importantly, this study showed that overfed subjects that increased NEAT did not store as much fat compared to subjects with lesser degrees of NEAT [4]. As an explanation, it is suggested that increasing NEAT allows excess energy to be dissipated thereby not allowing fat to store [4].

Another study by Wang and colleagues (2008) looked into the effect of physical activity in weight regain in overweight women [7]. In this study, 41 overweight women were randomly assigned to one of three groups:

- DIET

- DIET + Low Intensity Exercise

- DIET + High Intensity Exercise

In this study, exercise consisted of treadmill walking 3 days/week at a target heart rate [7]. For the low intensity exercise group, exercise progressed from 15-20 min at 45-50% of maximal heart rate the first week, to 55 min at the same maximal heart rate for the remaining study period [7]. The high intensity exercise group performed 30 min at 70-75% of maximal heart rate 3 days/week for the same duration [7]. All groups produced a caloric deficit of 400 kcal/day, while the DIET group created their deficit purely from dietary reduction [7].

At the end of the 20-week study period, resting metabolic rate marginally decreased on average by 7% (108 kcal/day) [7]. However, physical activity decreased on average by 26% (162 kcal/day) [7]. Also, physical activity decreased relative to body weight demonstrating that reductions in energy expenditure were associated with a decrease in movement not simply due to losses in body weight.

At 6-month follow-up, 31.5% of the weight loss during intervention was regained. At 12-month follow-up, this figure jumped to 51.4% weight regain [7]. Remarkably, women that showed the greatest decreases in physical activity after the study program had the largest weight regain [7]. Also, decreases in activity levels resulted outside formal exercise, indicating that decreases in NEAT were largely responsible for weight regain following the study period [7].

A NEAT Strategy for Weight Loss

Given the profound impact of NEAT on energy expenditure, increasing levels of non-formal activity can help greatly to facilitate weight loss goals and prevent weight regain. As demonstrated, selecting an activity such as light walking can significantly increase the number of calories expended compared to more sedentary activities like sitting and watching television [1].

Simple instruments like pedometers (i.e. Fitbit) are useful tools that can measure daily walking (i.e. steps, miles) to maintain elevated NEAT levels. Based on available evidence for pedometer-based activity, the following classification can be used for guidance [6]:

- <5,000 steps/daily – sedentary lifestyle

- 5,000 – 7,499 steps/daily – low active

- 7,500 – 9,999 steps/daily – somewhat active

- ≥10,000 steps/day – active

Summary

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis or NEAT is largely undervalued as a component of total daily energy expenditure. For the great majority of people living in developed countries, exercise activity thermogenesis, inclusive of NEAT, are negligible [1]. Even among those that participate in regular structured exercise, NEAT is still the largest component of activity thermogenesis [1]. Given that NEAT has the potential to impact TDEE up to 1,000 calories per day and can vary as much as 2,000 calories per day among people, more consideration must be given to its importance in weight management [2]. As a simple tool, pedometers can be used to track daily walking and used a practical strategy to improve total daily NEAT.

For more information on our personal training services please click here to read more.

References:

[1] Levine, J. A. et al. 2006. Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis. The Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon of Societal Weight Gain. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. April. Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 729-736.

[2] Levine, J. A. 2004. Nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): environment and biology. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism. May. Vol. 285. No. 5. E675-685.

[3] Levine, J. A. 2002. Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT). Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endrocrinology & Metabolism. December. Vol. 16, No. 4, 679-702.

[4] Levine, J. A. et al. 1999. Role of Nonexercise Activity Thermogenesis in Resistance to Fat Gain in Humans. Science. January. Vol. 283, No. 5399, pp. 212-214.

[5] Schuler, L. & Aragon, A. 2014. The Lean Muscle Diet. Rodale Inc. New York.

[6] Tudor-Locke, C. et al. 2011. How many steps/day are enough? For adults. The International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity. July. Vol. 8, No. 79, pp.1186-1479.

[7] Wange, X. et al. 2008. Weight Regain is Related to Decreases in Physical Activity During Weight Loss. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. October. Vol. 40, No. 10, pp. 1781-1788.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.