YOUR FITNESS BLOG

Post-Workout Nutrition: Is there An Anabolic Window?

Post-Workout Nutrition Rationale

The primary rationale for immediate post-workout nutrition is to replenish glycogen stores [1]. Glycogen is a storage form of carbohydrates (i.e. glucose) and the primary fuel source during moderate-repetition resistance exercise. Glycolysis, the breaking down of glucose, supplies as much as 80% of the energy during resistance exercise [1,13]. One study investigating muscle substrate utilisation during resistance exercise showed that just one set of arm curls performed to failure at 80% of 1 repetition-maximum (1RM) decreased muscle-glycogen stores by 12% [8]. Three sets at the same intensity reduced glycogen stores by 32% [8].

Glycogen has also been found to attenuate muscle protein breakdown [1]. This is accomplished through its insulin spiking effects, which is shown to reduce muscle degradation [5]. Following resistance exercise, muscle protein breakdown is elevated then rapidly rises thereafter lasting approximately 24 hours post-exercise [9]. Subjects performing resistance exercise under fasted conditions are found to exhibit peak muscle protein breakdown at just over 3 hours post-exercise [9]. Theses levels are further elevated by 30-50% three hours following strenuous exercise [6].

Finally, immediately post-workout nutrition is considered beneficial for elevating muscle protein synthesis [1]. Muscle protein synthesis refers to the building of new muscle protein, which forms the building blocks of muscle mass development [6]. The scientific literature reveals conflicting results when determining if immediate post-exercise consumption of protein, or carbohydrates, or a mixture of both enhances muscle protein synthesis. Some studies have demonstrated an increase in muscle protein synthesis with the immediate post-exercise consumption of primarily protein and carbohydrates, while others found no difference when protein and carbohydrates were ingested 1 hour versus 3 hours post-exercise [7, 11].

Origins of the “Anabolic Window”

The “anabolic window” is commonly referred to as the short period following a workout whereby muscular adaptations are considered compromised if nutrients (i.e. carbohydrates and protein) are not ingested. This theory was first brought to the mainstream by researchers John Ivy and Robert Portman.

The “anabolic window” is commonly referred to as the short period following a workout whereby muscular adaptations are considered compromised if nutrients (i.e. carbohydrates and protein) are not ingested. This theory was first brought to the mainstream by researchers John Ivy and Robert Portman.

Initiating the “faster is better” concept, Ivy and colleagues conducted a study in 1988 examining the effects of muscle glycogen synthesis following continuous cycling [3]. The authors exercised 12 male cyclists continuously for 70 minutes on a cycle ergometer at 68% VO2 max interspersing this with two, 2-minute bouts of higher intensity cycling at 88% VO2 max [3]. The subjects were fed a 25% (2g/kg) carbohydrate solution either immediately following exercise or 2 hours post-exercise [3].

The results of this study showed that glycogen synthesis was 3 times faster in the immediate consumption group compared to delayed intake [3]. At 4-hours post-exercise, glycogen synthesis was still approximately twice as fast in the immediate intake group than the delayed group [3]. As a result of these findings, Ivy and Portman suggested that immediate carbohydrate intake post-exercise was critical to replenish glycogen stores and maximise recovery [3, 4].

The same authors published a a book in 2004 called Nutrient Timing and in it provided guidelines that specific nutrients should be ingested within 45 minutes immediately post-exercise to prevent muscle breakdown and potential insulin resistance [4].

Limitations of Post-Workout Nutrition Guidelines

The book entitled Nutrient Timing (2004) by Ivy and Portman contains important limitations that should be considered when interpreting its recommendations for post-workout nutrient timing. The following limitations include:

- The majority of research cited in the book relates to over-night fasted subjects. Under circumstances of fasted, strenuous exercise, an increase in muscle protein breakdown does occur which extends net negative protein balance post-exercise [1]. However, in the majority of cases, exercise is not initiated in a fasted state. It is more common for individuals to have a meal or supplement within 3 hours of exercise.

- Recommendations were based largely on studies that examined endurance or depletion protocols. During endurance exercise (i.e. marathon, cycling) immediate post-workout nutrition to replenish glycogen is warranted given the requirement to perform for longer periods or multiple sessions in a day. This requirement would be similar for a lifter performing multiple resistance training sessions in a day utilising the same muscle groups. However, for the far majority of individuals, this requirement and the need for immediate glycogen replenishment does not exist.

- Studies used to inform recommendations were based primarily on acute study periods. Subjects in many of these studies were put through single session protocols. Longer study periods would be required to understand the true impact of immediate post-exercise ingestion of nutrients on glycogen synthesis.

Pre-Workout Nutrient Timing

Traditional recommendation for post-workout nutrition timing is to consume protein, or carbohydrates, or a mixture of both to elevate insulin and create a positive net protein balance [1]. However, sufficient and consistent evidence indicates that once insulin has been elevated to peak levels, its effects will continue for several hours beyond consumption {2, 10].

A study by Capaldo and colleagues (1999) showed that a mixed meal of 37g of protein, 75g of carbohydrates and 17g of fat elevated insulin levels 3 times above fasting levels in 30 minutes [2]. At 1 hour post consumption insulin levels were 5 times above fasting levels and at 5 hours insulin was still twice that of fasting levels [2].

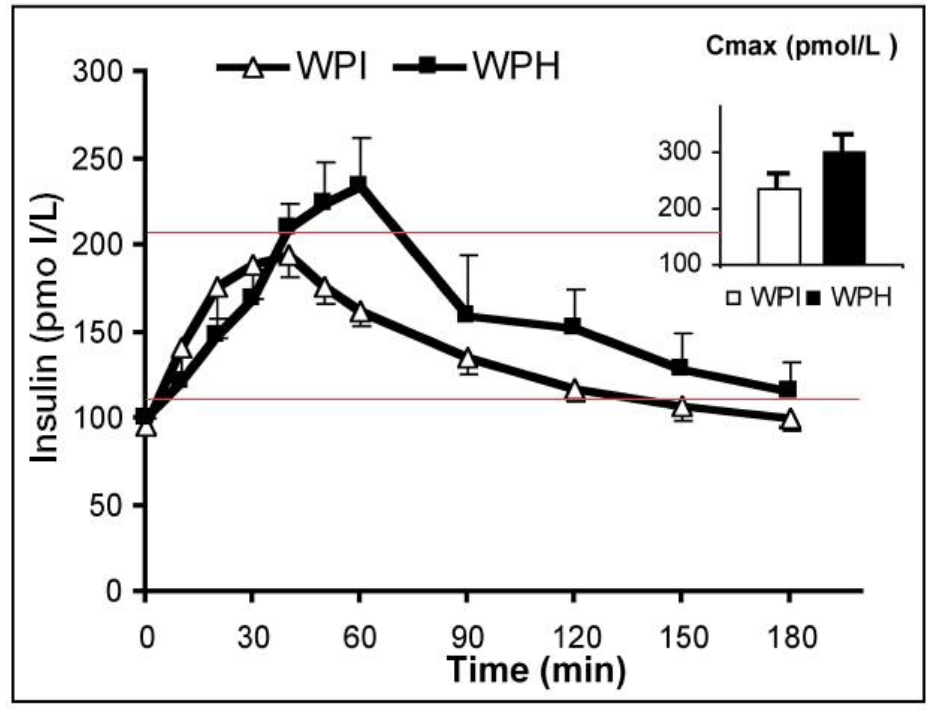

Moreover, the literature shows that insulin elevation will max out net muscle protein balance (protein synthesis minus protein breakdown) at 15-30 mU/L, which is approximately 3-4 times normal insulin levels [12]. A study by Power and colleagues (2009) showed that 45 grams of whey protein takes about 40 minutes to peak blood amino acids and keeps net muscle protein balance elevated at 15-30 mU/L for approximately two hours following [10]. In other words, attempting to increase insulin levels through ingestion of more protein or carbohydrates post-workout will not elevate levels beyond this limit.

Given a circumstance where an individual has consumed nutrients an hour or two prior to training, blood amino acid levels would remain elevated far beyond a typical 1-hour gym session, therefore making immediate post-workout nutrition completely redundant [1]. In this scenario, a meal consumed 1-2 hours pre-workout would be more than sufficient to ensure recovery and positive protein balance following a workout [1].

The “Muscle Full” Effect

There is a concept in the literature called the “muscle full” effect or protein refraction, which refers to the point where the ingestion of protein or amino acids cause muscle protein synthesis to peak, and no further increases in muscle protein synthesis can be achieved beyond this level [1]. Once peak amino acids levels are reached, muscle protein synthesis becomes refractory, or “full,” and additional amino acids are then relocated for oxidisation or alternative uses other than muscle protein synthesis [1]. Even though amino acids or protein may be available, muscle protein synthesis still returns to baseline levels within approximately 3 hours despite amino acid availability [1].

Based on this “muscle full” effect, it would be appropriate, under circumstances where a training session is undertaken 3 hours, or more, after a meal, to consume protein or a mixture of protein and carbohydrates immediately post-exercise to maximise recovery and muscle growth [1].

Summary

Traditional recommendations for immediate post-workout nutrition to maximise recovery and muscle growth is far from supported by the literature. Only under circumstances where exercise is performed under a fasted state or multiple bouts of exercise are performed within a day would immediate post-workout nutrient be required. Given the findings, emphasis should be placed on the timing and composition of the pre-workout meal.

A pre-workout protein supplement (20g-40g) or mixed meal consumed approximately 1-3 hours prior to a training session is sufficient to raise blood amino acid levels for at least 3-6 post-exercise making immediate post-workout nutritional intake redundant. As an evidence-based guideline, the duration between pre- and post-workout meals should be about 3-4 hours [1]. The consumption of a larger pre-workout mixed meal would theoretically extend this interval even further (i.e. 5-6 hours) [1].

For more information on our personal training services please click here to read more.

References:

[1] Aaragon, A. A. & Schoenfeld, B. J. 2013. Nutrient timing revisited: is there a post-exercise anabolic window? Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. January. Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 1550-2783-10-5.

[2] Capaldo B. et al. 1999. Splanchnic and leg substrate exchange after ingestion of a natural mixed meal in humans. Diabetes. May. Vol. 48, No. 5, pp. 958–966.

[3] Ivy, J. L. et al. Muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise: effect of time of carbohydrate ingestion. Journal of Applied Physiology. April. Vol. 64, No. 4, pp. 1480-1485.

[4] Ivy, J. L. & Portman, R. 2004. Nutrient timing: The future of sports nutrition. California: Basic Health Publications, Inc.

[5] Kettelhut, J. C. et al. 1988. Endocrine regulation of protein breakdown in skeletal muscle. Diabetes/Metabolism Reviews. December. Vol. 4, No. 8, pp. 751-772.

[6] Kumar, V. et al. 1985. Human muscle protein synthesis and breakdown during and after exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology. June. Vol. 106, No. 6, pp. 2026-2039.

[7] Levenhagen, D. K. 2001. Postexercise nutrient intake timing in humans is critical to recovery of leg glucose and protein homeostasis. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism. June. Vol. 280, No. 6, E982-983.

[8] McDougall, J. D. et al. 1999. Muscle substrate utilization and lactate production. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology. June. Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 209-215.

[9] Pitkanen, H. T. et al. 2003. Free amino acid pool and muscle protein balance after resistance exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. May. Vol. 35, No. 5, pp. 784-792.

[10] Power, O. et al. 2009. Human insulinotropic response to oral ingestion of native and hydrolysed whey protein. Amino Acids. Vol. 37, No. 2, pp.333–339.

[11] Rasmussen, B. B. et al. 2000. An oral essential amino acid-carbohydrate supplement enhances muscle protein anabolism after resistance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology. February. Vol. 88, No. 2, pp. 386-392.

[12] Rennie, M. J. et al. 2006. Branched-chain amino acids as fuels and anabolic signals in human muscle. The Journal of Nutrition. Vol. 136 (1 Suppl):264S–8S.

[13] Schoenfeld, B. J. 2013. The M.A.X. Muscle Plan. Leeds: Human Kinetics.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.