YOUR FITNESS BLOG

Low-FODMAP Eating May Help You, Here's How

For those individuals who have suffered from irritable bowl syndrome (IBS) or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the road to becoming healthier and fitter is immediately made more challenging. Nutrition has found to play an integral role in triggering symptoms of IBS and IBD with about 60% of patients reporting that certain foods exacerbate their symptoms [4]. Due to the symptomatic diversity of IBS, pharmacological treatments are often ineffective, targeting only primary symptoms while a host of other symptoms are present. Considering the potential role of food and trigger foods in symptomatic exacerbation of IBS and IBD, specific dietary alterations, like a low-FODMAP diet, have been found to greatly improve symptoms and overall quality of life [4, 5].

What Are IBS and IBD?

IBS is a chronic gastrointestinal disease that affects between 7% and 15% of the population [4]. It is characterized by symptoms like abdominal pain or discomfort, altered bowel habits, bloating and abdominal distention. IBD is inflammation of the small and large intestine and affects 1 in 250 people in the United Kingdom [3]. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis together are the most common forms of inflammatory bowel diseases and are similarly characterized by abdominal pain, bloating (distension), constipation, diarrhoea and gas [8].

What Causes IBS and IBD?

Unfortunately, the cause of IBS and IBD are not completely understood and are thought to be a result of a combination of altered gut microbiota (reduced diversity of intestinal flora), visceral hypersensitivity (pain within the inner organs), and changes in gastrointestinal motility (movement of waste through the gastrointestinal tract) and low-grade inflammation [4].

What Can We Do About It?

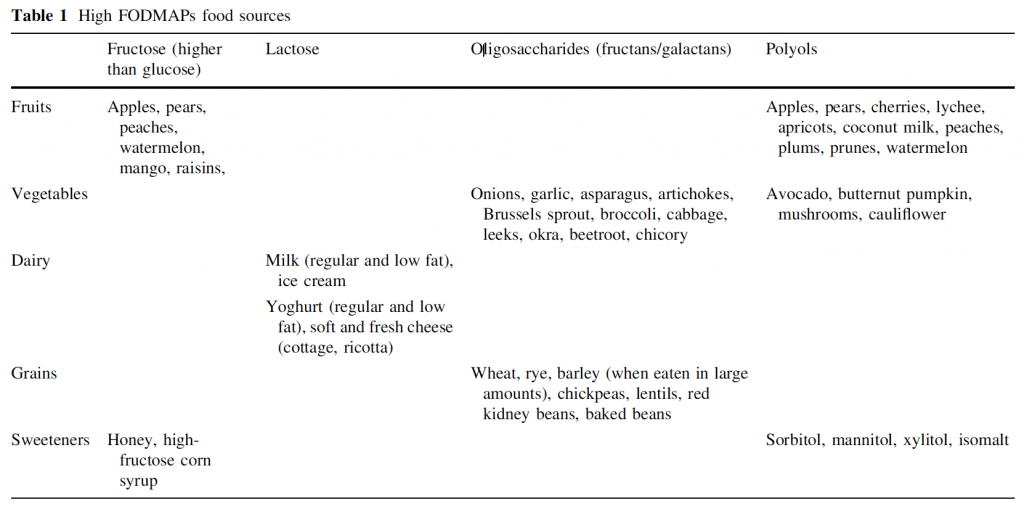

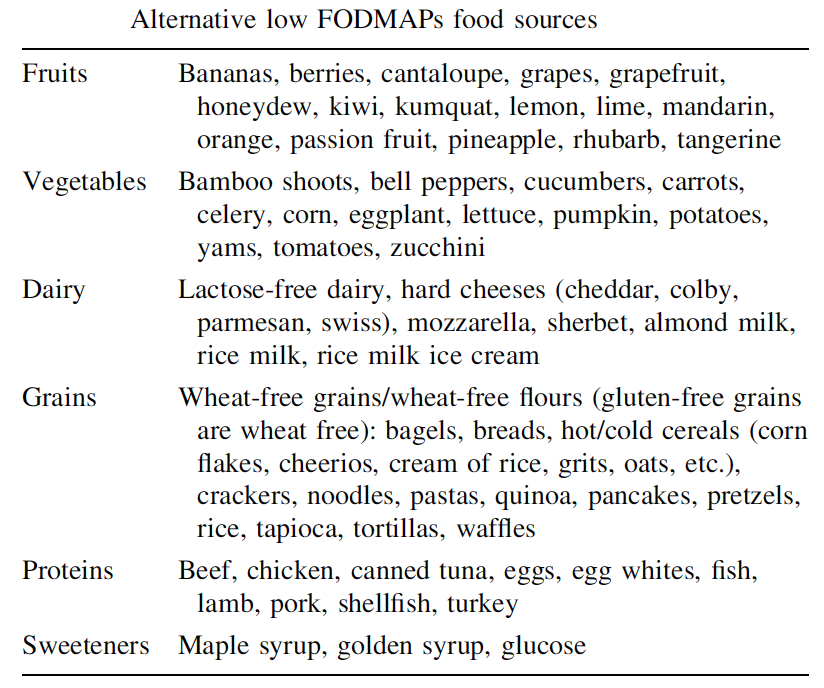

More recently, researchers have investigated an elimination diet that aims to minimize symptoms of IBS called the low-FODMAP diet. FODMAP is an acronym used to define a group of fermentable, short-chain carbohydrates including fermented oligosaccharides (fructans and galactans), disaccharides (lactose), monosaccharides (fructose in excess of glucose), and polyols (sorbitol, mannitol etc.) [5].

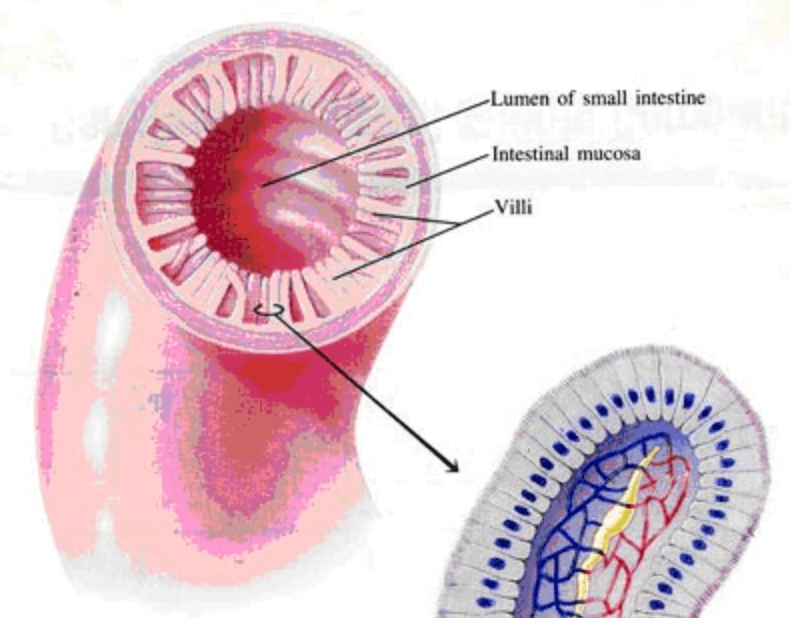

The low-FODMAP eating pattern is based on the physiology that in humans, short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) are poorly absorbed and broken down in the small intestine, which increases the fluid load in the colon and gas production [5]. Also, gas generated during the fermentation of FODMAP foods adds to the filling of gas in the colon, which as a result may cause bloating and abdominal distension. The open space in the colon called the lumen, fills with gas, which then activates gastrointestinal movement and the transit of waste contents within the colon, which may accelerate transit and contribute diarrhoea or subjectively perceived spasms [5].

Another mechanism whereby FODMAPs create gastrointestinal symptoms is through changes in intestinal fluid content within the lumen [5]. Diets rich in FODMAPs were shown to lead to increases in waste weight and water content leading to accelerated gut motility [5]. Also, subjects placed on high-FODMAP diets were found to have increased hydrogen concentrations in the lumen of the digestive tract, which correlated with increased gas in the colon and further suggests that fermentable foods may alter gut flora [7].

Low-FODMAP Diets: What’s The Evidence?

A randomized crossover study by Ong and colleagues in 2010, randomized 15 subjects with IBS and 15 healthy controls to a low or high-FODMAP diet for 2 days. The study used gastrointestinal symptoms and hydrogen gas samples (a marker of gas in the colon) as outcome measures. Subject on the high-FODMAP diet experienced worsening abdominal bloating and pain, gas, nausea, heartburn and fatigue, whereas subjects on low-FODMAP experienced an increase in only gas. Also, the subject on the high-FODMAP diet showed higher hydrogen levels compared to the low-FODMAP subjects [6].

A single-blinded randomized controlled trial by Staudacher and colleagues (2012) investigated the effects of a 4-week low-FODMAP diet on changes in microorganisms in the lumen of the digestive tract, short-chain fatty acids, and gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects with IBS. A total of 35 subjects were randomly allocated to either a low-FODMAP group or habitual diet (control) group. A stool sample was collected and analyzed for bacteria groups. At follow-up, the low-FODMAP group had a lower intake of short-chain fatty acids, the total bacteria in the lumen of the digestive tract did not differ between groups, and more patients in the intervention (low-FODMAP) group reported adequate control of symptoms (13/19, 68%) compared with controls (5/22, 23%) [7].

A 2013 randomized crossover study by Biesiekierski and colleagues looked at the impact of a 2-week low-FODMAP diet on 37 patients with IBS that fit the criteria for “non-celiac gluten sensitivity.” Subjects were placed on a low-FODMAP diet for 2-weeks then randomly allocated to high-gluten, low-gluten or whey protein diets for 1-week. The study used a 100-point visual analogue scale (VAS) and significant worsening of symptoms was indicated by a 20-point change in the VAS. All subjects that were placed on the low-FODMAP diet reported significant symptomatic improvement, which worsened with any addition of either gluten or whey protein to their diet [1].

A recent (2015) systematic review and meta-analysis by Marsh and colleagues, examined 6 randomized controlled trials and 16 non-randomized interventions aimed at determining the efficacy of a low-FODMAP diet on the treatment of functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Outcome measures included a reduction in the Symptoms Severity Score (SSS) and increases in the IBS Quality of Life (QOL) score. Analysis of the 22 studies showed a significant decrease in IBS SSS scores for those subjects on a low-FODMAP diet in both the randomised controlled and non-randomised intervention studies [4].

Summary

There is adequate evidence to suggest that adopting a low-FODMAP way of eating can significantly improve gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, gas, and diarrhea in those individuals suffering from IBS or IBD. Individuals that have conditions like small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) would also benefit from a low-FODMAP nutrition plan, as FODMAP foods need to pass through the small intestine and would feed already overgrown bacteria in small intestine potentially exacerbating the condition.

However, there is evidence that indicates that adherence to a low-FODMAP diet may lower concentrations of beneficial bacteria in the colon like bifidobacteria, which can be obtained from FODMAP foods [7]. The question would then be how long to practice a low-FODMAP diet as to not produce a damaging effect on the gastrointestinal microbiota (gut flora). Implications of a low-FODAMP diet on gut microbiota still need further investigation to accurately answer this question.

For more information on our services please click here to read more.

References:

1. Biesiekierski, et al. 2013. No effects of gluten in patients with self- reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. August. Vol. 145, No. 2, pp. 320-328.

2. Halmos, E. P. et al. 2014. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. January, Vol. 146, No.1, pp. 67-75.

3. IBD Scotland. 2015. What is IBD? [online] [Viewed 20 December 2015]. Available from: http://www.ibdscotland.org/content/what-ibd.

4. Marsh, A., Eslick, E. M. & Eslick, G. D. 2015. Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta?analysis. European Journal of Nutrition. May.

5. Muhammed, A. K. et al. 2015. Low-FODMAP Diet for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Is It Ready for Prime Time? Digestive Diseases and Sciences. May, Vol. 60, No. 5, pp. 1167-1177.

6. Ong, D. K. et al. 2010. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. August, Vol. 25, No. 8, pp. 1366-1373.

7. Staudacher, H. M. et al. 2012. Fermentable Carbohydrate Restriction Reduces Luminal Bifidobacteria and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Irritable

Bowel Syndrome. The Journal of Nutrition. August, Vol. 142, No. 8, pp. 1510-1518.

8. Stein, D. A. & Shaker, R. 2015. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Point of Care Clinical Guide [online]. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing [Viewed 20 December 2015]. Available from: http://www.springer.com/la/book/9783319140711.

9. Wolf, W. A., Kiraly, L. N. & Ireton-Jones, C. 2015. Incorporating FODMAP Dietary Restrictions: Help or Hype? Gastroenterology and Nutrition. September, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 214-219.

10. Yoon et al. 2015. Low-FODMAP formula improves diarrhea and nutritional status in hospitalized patients receiving enteral nutrition: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind clinical trial. Nutritional Journal. November, Vol. 14, No. 1, p. 116.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.