YOUR FITNESS BLOG

Low-Carbohydrate Diets: Can they help with fat loss?

Introduction

Carbohydrates are one of three macronutrients (protein and fat being the other two) that are found in food. Broadly speaking, carbohydrates can be subdivided into three groups: sugars, starch, and dietary fiber. These groups include carbohydrates foods like fruits and white sugar, potatoes, breads, and pasta, and fruits and vegetables, beans and lentils. Carbohydrates have long been demonised by the media and both fitness and health professionals. Popular low-carbohydrate diets like The Atkins diet labelled carbohydrates as “fattening” and made claims that carbohydrates themselves, not calories, are responsible for weight gain [4, 5]. Other low-carb diets like the ketogenic diet (high fat, low carb) claim to posses a significant metabolic advantage for body composition in accelerating weight loss compared with high-carbohydrate diets. Despite the continued popularity of low-carbohydrate diets, experimental evidence does not support such claims [3, 4, 6, 10]. This article will discuss the “carbohydrate-insulin model” and examine the scientific literature to understand whether low-carbohydrate diets are associated with metabolic changes that would benefit fat loss.

The Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Obesity

When carbohydrates are eaten (i.e. fruits, vegetables, grains), a hormone called insulin is released from the pancreas, an organ located behind the stomach [5, 11]. Among other functions, insulin’s primary function is to regulate blood sugar levels [11]. It does this by transporting glucose from the blood into tissues such as muscle, fat, and liver, among others [11]. In healthy individuals, when carbohydrates are eaten, glucose (a simple sugar found mostly in plant foods) enters the blood and the pancreas senses this increase in glucose and releases insulin, which then brings blood glucose back down to normal levels [8, 11]. Once blood glucose goes back down, insulin also goes down [8, 11]. This is a normal cycle and happens every time we eat [8, 11].

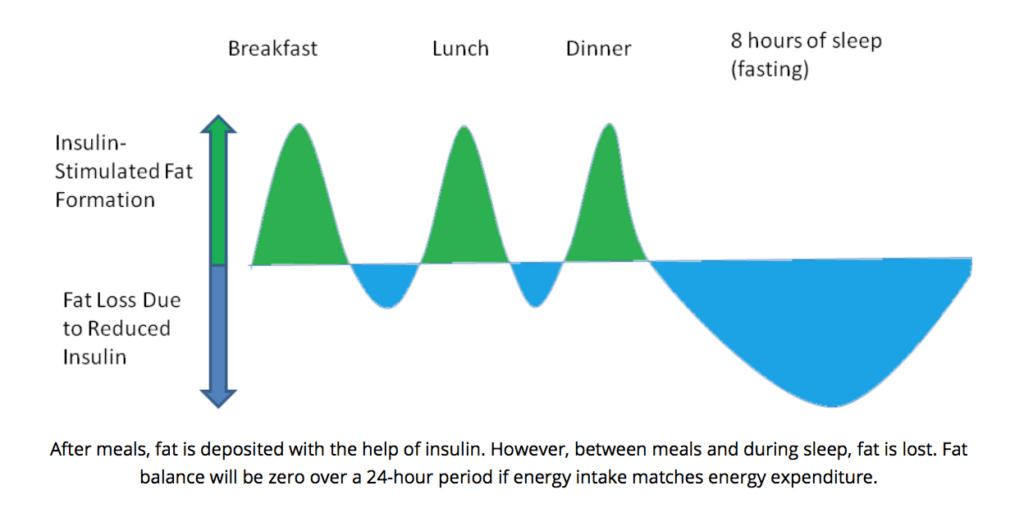

In addition to the role insulin plays in controlling blood glucose, it also inhibits lipolysis, which is the process where triglycerides (the main components of fat) are broken down [7, 11]. Insulin also functions to stimulate lipogenesis, which is the building of fat [7, 11]. It is this observation that dietary carbohydrates increases insulin, which leads to decreased lipolysis (fat breakdown) and increased lipogenesis (fat creation), that have led to the hypothesis that carbohydrates are “fattening.”

Specifically, the ‘carbohydrate-insulin model’ has been used to argue that carbohydrates cause weight gain and obesity [5]. Proponents of the carbohydrate-insulin model suggest that consuming a high proportion of dietary carbohydrates elevate insulin and consequently “trap” free fatty acids from being released from fat cells (adipose tissue) and being used by metabolically active tissue like organs [4, 5]. The argument is that people then overeat because other tissues (i.e. muscles, heart, liver) cannot gain enough energy because of these “trapped” fats [4, 5, 6]. Therefore, according to this model, consuming excess calories is a result of fat tissue storage due to the increased insulin effect from carbohydrates.

In line with this model, decreasing dietary carbohydrates will then reduce insulin secretion, increase fat mobilisation, and elevate the burning of free fatty acids [4, 5, 6]. It is proposed that a reduction in carbohydrates would lead to an increase in energy expenditure amounting to approximately 300-600 calories per day [4, 5]. This increase in energy expenditure would thereby result in accelerating fat loss efforts. In contrast to the carbohydrate-insulin model, a more conventional model argues that, essentially, a calorie is a calorie, meaning that changes in dietary carbohydrates or fat will not significantly change energy expenditure or body fat provided the calories in both carbohydrates and fat are equal [4, 5, 6].

A Look Into The Research

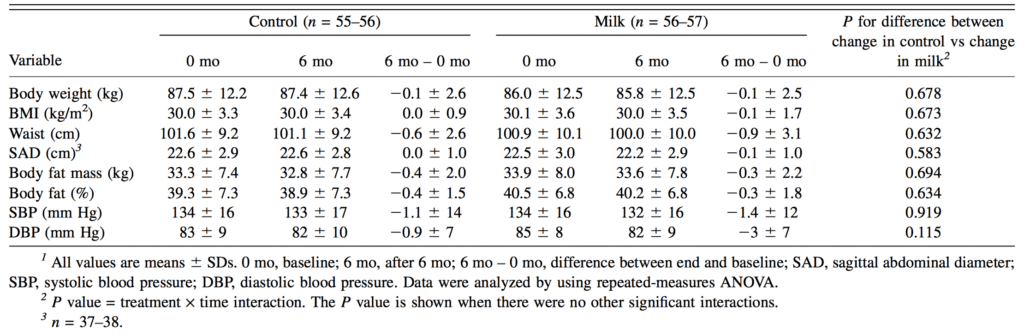

If the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis were true, and insulin was preventing fat breakdown, then all foods that produced a high insulin response would promote fat gain. The macronutrient protein has been shown in many studies to increase insulin levels similar to carbohydrates [1, 2]. Yet, higher protein diets have been shown to be beneficial for body composition [2, 13]. Also, dairy foods are found to have a high insulin response [9]. Wennerserbery and colleagues (2009) published a study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition in 2009 that looked at impact of a increasing dairy intake on body composition [12]. In their study, the authors took 122 middle-aged, overweight individuals and randomly assigned them for 6-months to ether a normal diary group, or a high dairy group [12]. The normal dairy group were asked to continue with their current diet and not change their intake of dairy, while the high dairy group were instructed to include 3-5 portions of dairy products per day [12]. The increase in dairy primarily came from foods like milk, yogurt, and cheese [12]. The authors assessed body composition using dual-energy X-Ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and bioimpedenace [12].

Over the 6-month study period, the increase in dairy products in the high dairy group was associated with an increase in average calories as well as a higher intake of protein, fat (especially saturated fat), cholesterol, and calcium [12]. Despite these increases, there were no significant changes between groups in body weight, abdominal fat, or body fat [12].

Notably, over the study period, insulin levels between the normal and high dairy groups were not significantly different [12]. It is argued that a high carbohydrate leads to chronically high insulin levels, which results in more fat accumulation, because lipogenesis (fat creation) remains higher than lipogenesis (fat breakdown) [8]. However, insulin, and subsequently lipogenesis, only increase following meals [7, 8]. During the period between meals (fasting), lipogenesis (fat breakdown) will be greater than lipogenesis (fat creation) [8]. Therefore, over an entire day, the period of fat burning and gaining will balance out [8]. This could explain why the authors in the aforementioned study did not see increases in insulin levels in the high dairy group from baseline to post-study at 6-months.

High Carbohydrates Versus Low Carbohydrate Diets

If carbohydrates are genuinely the cause of weight gain and obesity, then diets that are equal in calories and protein, should show advantages for fat loss in low-carb diets compared with higher-carb diets. Dietary protein would need to be equated between diets because protein has been shown to increase energy expenditure, therefore offering an advantage for body composition [1, 13].

A number of studies have examined whether a metabolic advantage exists with low carbohydrate diets, comparing high-carb with low-carb [3, 6, 10]. A meta-analysis conducted by obesity researcher and physicist Kevin Hall and Guo (2017) published in Gastroenterology, pooled together all studies that compared low-carbohydrate diets to relatively higher carbohydrate diets to understand the effects on energy expenditure and body fat [4]. In their study, the authors only accepted studies that matched calories and protein intake and varied their ratio of dietary carbohydrates and fats [4]. Also, to combat the issue of dietary non-adherence in their selected studies, the authors only included studies that controlled feeding where food was provided to subjects [4]. This meta-analysis included at total of 32 studies composed of 563 subjects [4].

When examining energy expenditure differences between low-carb, high-fat diets compared with high-carb, low-fat diets, the authors found no significant differences between both diets [4]. Similarly, when examining whether an advantage exists with body fat with lower carbohydrate diets compared with lower fat diets, there was no significant difference [4]. In fact, there was a slight advantage in energy expenditure (26 calories more) and fat loss (16 grams more) with higher carbohydrate, lower fat diets compared with lower carb, higher fat [4]. The authors noted that “these results are in the opposite direction to the predictions of the carbohydrate-insulin model” and for all practical purposes “a calorie is a calorie [4].”

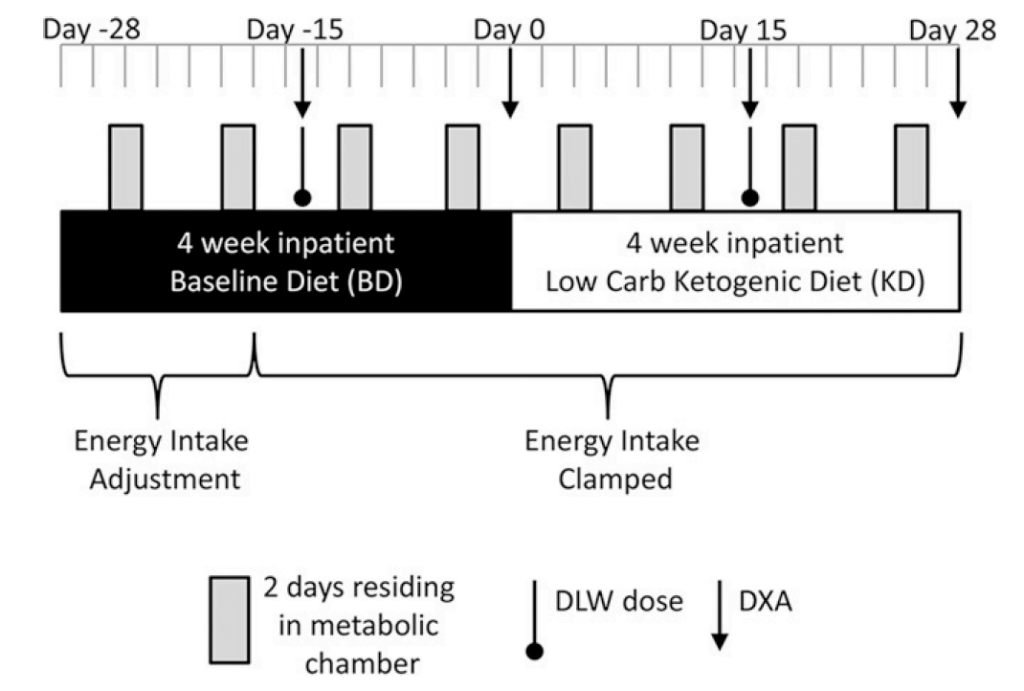

In an independent study by Hall and colleagues published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition in 2016, the authors completed a well controlled study to investigate whether a diet low in carbohydrates differed in energy expenditure and body composition compared with a calorie equated high-carbohydrate diet [6]. In this study, the authors took 17 obese or overweight men and admitted them to a metabolic ward where feeding could be tightly controlled [6]. The subjects were placed on a 7-week high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet (ketogenic diet) that contained 2,398 calories, 91 grams protein, 300 grams carbohydrates, and 93 grams of fat, followed by a 7-week low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet that contained 2,394 calories, 91 grams protein, 31 grams carbohydrates, and 212 grams of fat [6].

On the high-carb, low-fat diet, subjects lost 0.8kg of body weight with 0.5kg coming from body fat [6]. During the low-carb, high-fat diet, subjects lost a rapid 1.6kg of body weight, however only 0.2kg came from body fat [6]. Transitioning from the high-carb to the low-carb diet, subjects experienced a substantial decrease in insulin secretion, an increase in circulating free fatty acids, ketones, as well as a small increase in energy expenditure of about 100 calories per day [6]. Importantly, however, these changes were not accompanied by greater losses in body fat [6]. As each gram of stored carbohydrate, called glycogen, is attached to 3-4 grams of water, the authors noted that the initial, rapid loss of body weight subjects experienced on the low carb diet was primarily the result of water loss, as fat loss was slower than in the high carbohydrate diet [6]. These results directly oppose the carbohydrate-insulin model and are more in line with conventional views that manipulating carbohydrates or fat make little difference to energy expenditure or fat loss when calories and protein intake are equated.

Summary

The argument that low-carbohydrate diets result in body-fat gain relates to the carbohydrate-insulin model, which suggest that carbohydrate containing foods release high levels of insulin, which promote energy storage and prevent its release. Although insulin plays an important role in regulating body fat, the carbohydrate-insulin model has been refuted in a number of studies. Instead, studies that equate calories and protein intake show no advantage for fat loss whether carbohydrate intake is low or high. The weight of the evidence support more of a conventional view that “a calorie is a calorie” in the context of body fat and energy expenditure. In line with a conventional model, provided total calories are within what is required for an energy deficit and fat loss, the manipulation of carbohydrates or fat are inconsequential. Priority should of be placed on creating an energy deficit where within, more personal preference can be applied for the proportion of carbohydrates and fats.

For more information on our personal training service please click here to learn more.

References:

[1] Bray, G. A, et al. 2012. Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: a randomized controlled trial. January. Vol. 307, No. 1, pp. 47–55. JAMA.

[2] Comerford, B. K. and Pasin, G. 2016. Emerging Evidence for the Importance of Dietary Protein Source on Glucoregulatory Markers and Type 2 Diabetes: Different Effects of Dairy, Meat, Fish, Egg, and Plant Protein Foods. August. Vol. 8, No. 8, p. 446. Nutrient.

[3] Dirlewanger, M. et al. 2000. Effects of short-term carbohydrate or fat overfeeding on energy expenditure and plasma leptin concentrations in healthy female subjects. November. Vol. 24, No. 11, pp. 1413-1418. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders.

[4] Hall, D. K. and Guo, J. 2017. Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition. May. Vol. 152, No. 7. pp. 1727-1727. Gastroenterology.

[5] Hall, D. K. 2017. A review of the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity. March. Vol. 71, No. 3, pp. 323-326. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

[6] Hall, D. K. et al. 2016. Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men. August. Vol. 104, No. 2, pp. 324-333. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

[7] Kersten, S. 2001. Mechanisms of nutritional and hormonal regulation of lipogenesis. April. Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 282-286. EMBO Reports.

[8] Krieger, J. 2010. Insulin An Undeserved Bad Reputation. Weightololgy. Taken From: https://weightology.net/insulin-an-undeserved-bad-reputation/.

[9] Nilsson, M. et al. 2004. Glycemia and insulinemia in healthy subjects after lactose-equivalent meals of milk and other food proteins: the role of plasma amino acids and incretins. November. Vol. 80, No. 5, pp. 1246-1253. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

[10] Schrauwen, P. et al. 2000. Fat and carbohydrate balances during adaptation to a high-fat diet. November. Vol. 72, No. 5, pp.1239-1241. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

[11] Vargas, E. et al. 2021. Biochemistry, Insulin Metabolic Effects. January. StatPearls.

[12] Wennersbery, H. M. et al. 2009. Dairy products and metabolic effects in overweight men and women: results from a 6-mo intervention study. October. Vol. 90, No. 4, pp. 960-968. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

[13] Wycherley, T. P. et al. 2012. Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Vol. 96, No. 6, pp. 1281–1298. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.