YOUR FITNESS BLOG

Let's Improve Your Motivation To Exercise!

Introduction

Motivation is defined as the desire or willingness of someone to engage in a particular behaviour [1]. Motivation to exercise is one of the greatest factors contributing to the initiation and consistency to exercise. Within the context of exercise, people commonly struggle to find the effort, energy, and persistence to maintain the essential consistency to see and feel short and long term benefit. Various types of motivation have been strongly linked to the amount of effort an individual expends during exercise in addition to intentions to remain consistent exercising [1, 2, 4].

In health and fitness, people are often motivated by external factors such as weight loss or fear of judgement or ridicule from others [1]. Conversely, people can be motivated from within, intrinsically, from sheer joy or satisfaction of exercise [1]. If specific motivational forces can be identified among those that are consistent at exercise, it would be possible to target these these types of motivation to improve exercise adherence. This article will examine motivation from a theoretical perspective and look to the research to identify the types of motivation people apply to remain consistent at exercise.

Self-Determination Motivation Continuum

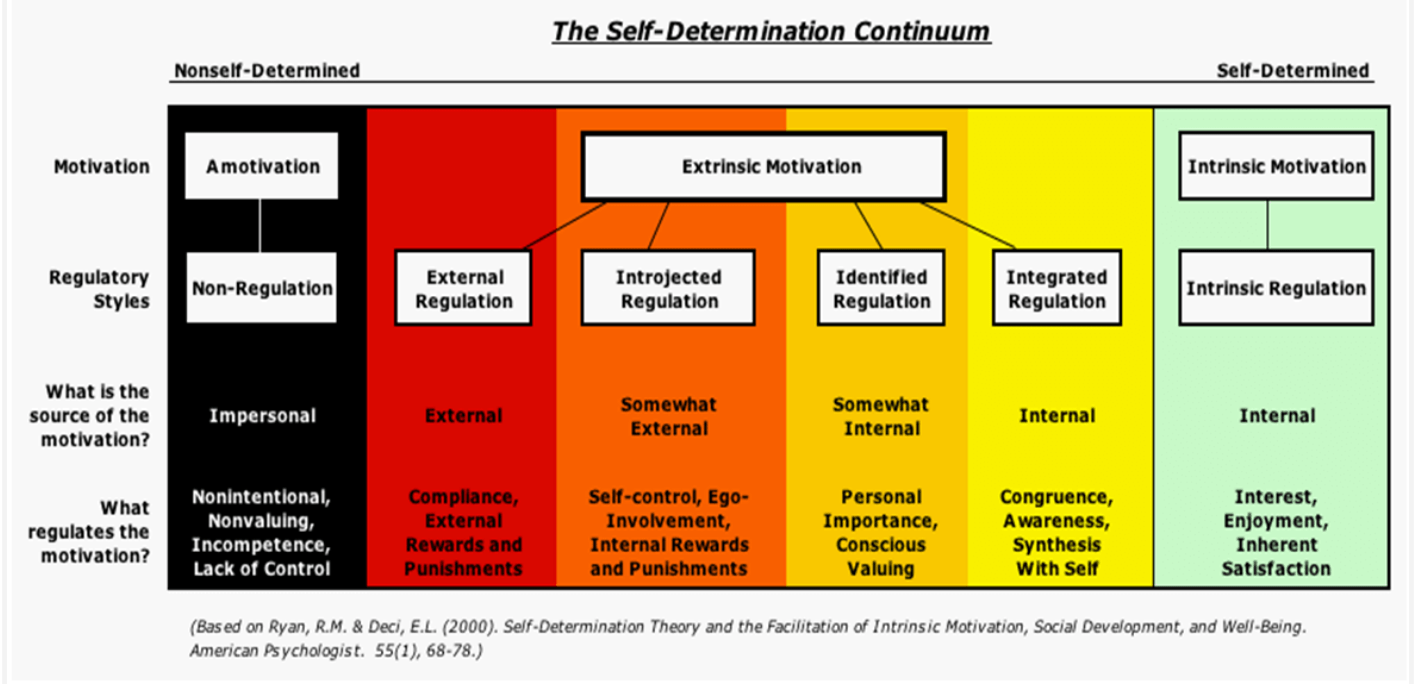

In order to understand the relationship between motivation and exercise behaviours such as frequency, intensity and duration, we use a formal theoretical framework called the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [3, 4]. SDT is a way of understanding motivation and has been frequently applied in exercise [1]. This framework stems from work completed by researchers Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan in the 19070’s and 1980’s [3, 4]. SDT posits there two main types of motivation: extrinsic and intrinsic [2, 3, 4].

Extrinsic motivation is the desire or drive to behave in ways because of external reasons [1, 3]. Extrinsic motivation is applied when there is reward involved, or because of evaluation, admiration or fear of others [1, 3]. In exercise, someone that is extrinsically motivated may exercise because of a weight loss result, or because his or her doctor indicates the negative consequence of not exercising. In contrast, intrinsic motivation comes from reasons within [1]. Internally motivated individuals are driven by reasons like core values, personal satisfaction, and identity connection [1, 4].

Instead of thinking about motivation as dichotomous, either extrinsic or intrinsic, it’s best to think of motivation on a continuum with varying degrees of motivation falling in between [1, 3]. On the far left of this continuum is amotivation where an individual completely lacks any motivation, has no drive, and feels like he or she lacks any autonomy is his or her actions [3, 4]. Autonomy refers to behaviours that are freely initiated by an individual [1, 3].

Four key motivation regulations make up the extrinsic motivation continuum [3, 4]. Each regulation successively increases in autonomy, moving from completely non-autonomous to self-aware. To the right of amotivation falls external regulation. External regulation is extrinsic and refers to motivation that is regulated by external reward, punishment, compliance or conformity [3, 4]. For example, someone that exhibits external regulation exercises because he or she is instructed to by their doctor.

The next type of motivation is introjected regulation. Introjected regulation is still predominantly externally motivated [1, 3, 4]. Here an individual is driven by intrapersonal rewards such as pride or ego, or to avoid punishment like shame or guilt [1].

The self-determination continuum then moves to become more internal in motivation with identified regulation [1, 3]. Identified regulation refers to being driven by reasons personally important to an individual [1]. For example, an individual might perform resistance exercise because they know it helps build lean muscle which mitigates muscle loss as we age.

The final motivational type, still external in nature, is integrated regulation. Integrated regulation is where an individual is motivated to perform a behaviour because this behaviour is part of his or her identity or consistent with his or her personal values [5, 6]. For example, an individual may exercise because he or she believes they are someone who exercises regularly and exercising is consistent with his or her identity [5, 6].

Finally, intrinsic motivation falls to the far right of this continuum and represents the most autonomous and self-determined form of motivation [1]. Here an individual is completely self-motivated and driven by true pleasure, satisfaction, interest or enjoyment of the behaviour [1, 5]. For example, an individual may run because they enjoy the feeling of running, or may perform yoga because it gives great satisfaction [1].

Motivation In Exercise Research

Research examining the association between motivation and exercise behaviours (i.e. frequency) show that people who tend to perform exercise more regularly exhibit more autonomy and self-determination [2, 4, 5, 6]. Li (1999) tested the theoretical basis of the self-determination model of motivation against 598 male and female college students that engaged in various exercises such as weight lifting, swimming, jogging and aerobics [2]. In their study, subjects were given a multiple-choice and open ended questionnaire that required subjects to answer questions such as [2]:

- “Why do you presently participate in exercise activities such as weight training,…?”

- “Why do your friends participate in exercise activities such as the ones just described?”

Responses from the questionnaire were assessed by a panel that determined for each response whether reason given was indicative of a category label within the self-determination theoretical model (i.e. interjected regulation) [2]. Results showed that intrinsic motivation was most positively linked to exercise effort and interest [2]. These were the individuals likely to exercise more frequently. In contrast, the sub-form of external motivation, called external regulation, were negatively associated with autonomy [2].

Specifically, introjected regulation was found to be positively related to perceptions of autonomy and competence with exercise [2]. Interesting, females reported greater levels of autonomy and intrinsic motivation, while males were more amotivated and motivated by external reward [2].

Wilson and colleagues (2004) conducted a study to understand the association between each regulation category within the self-determination theory and different exercise behaviours [6]. Specifically, the authors evaluated the association between each regulatory construct and current exercise behaviour, importance and effort placed on exercise, and intentions to continue exercise over the following 4 months in men and women [6]. Questionnaires were used to assess each area of exercise behaviour [6].

Results from this study showed a clear connection between autonomous regulation (identified and intrinsic) and exercise behaviours [6]. Intrinsic motivation was the strongest predictor of the importance and effort ascribed to exercise in both men and women [6]. Moreover, subjects that scored the highest in identified regulation were strongly associated with positive outcomes in all exercise behaviours [6].

Similar to the Li (1999) study, introjected regulation was found to be a positive predictor of all exercise behaviours, although more among females compared to males [2, 6]. This indicates that females, more than males, may demonstrate a greater sense of pride performing exercise or some form of guilt if they fail to exercise [1, 6].

Duncan and colleagues (2010) conducted a study to test the self-determination theory framework against various exercise behaviours (intensity, frequency and duration) [1]. Using a subject sample of 1054 students, the authors used self-reported questionnaires for all exercise behaviours [1]. Results confirmed findings from the aforementioned studies, showing that for both male and females, intrinsic motivation was the strongest predictor of exercise behaviours [1]. In both men and women, integrated and identified regulations were strong predictors of exercise frequency [1]. Similarly, integrated regulation was positively associated with exercise duration in both genders [1]. Among females, this study found that introjected regulation was a positive predictor of exercise intensity [1].

Importantly, integrated regulation was the most significant predictor of exercise duration in both males and females [1]. As previously noted, integrated regulation is the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation that involves connecting exercise to one’s identity [1, 2, 5, 6]. This indicates that an individual is more likely to exercise longer if he or she feels like the exercise engaged upon is consistent with his or her identify [1].

Summary

Motivation to exercise is undoubtably a powerful influence on exercise behaviours like frequency, duration, intensity, importance and effort [1, 5, 6]. The self-determination theory provides a framework to better understand the varying degrees of motivation within exercise. The self-determination theory suggests that motivation falls on a continuum made up of intrinsic and extrinsic components with varying degrees of autonomy [1]. The scientific literature points to more autonomous forms of motivation as stronger, positive predictors within all exercise behaviours [1, 5, 6].

Among individuals who exercise consistently (at least twice each week) and for longer, identified and integrated regulations appear to be most relevant [1, 3, 5]. Also, intrinsic motivation is found to associate with greater effort and importance placed on exercise [1, 2, 6]. As identified and integrated forms of motivation involve identity and value connection, individuals and personal trainers should focus on incorporating exercise into his or her personal value’s and creating an identity that says “I am an exerciser” and “this is who I am. [1]”

Even among individuals new to exercise, integrated regulation can be reinforced through exercise-related goal setting and self-monitoring to track goal attainment progress [1]. Self-monitoring of exercise (i.e. workout records), nutrition (i.e. food tracking), and general movement (i.e. step counting) can all be used to support exercise identify connection [1].

For more information on our personal training services please click here to read more.

References:

[1] Duncan et al. 2010. Exercise motivation: A cross-sectional analysis examining its relationships with frequency, intensity, and duration of exercise. January. Vol. 7, No. 7. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition.

[2] Li, F. 1999. The exercise motivation scale. Its multifaceted structure and construct validity. April. Vol. 11, pp. 97-115. Journal of Applied Sport Physiology.

[3] Mullan, E. and Markland, D. 1997. Variations in self-determination across stages of change for exercise in adults. December. Vol. 21, Issue 4, pp. 359-362. Motivation and Emotion.

[4] Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. 1995. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. January. Vol 55, No. 1, pp. 68-78. American Psychologist.

[5] Wilson, P.M. et al. 2006. “Its who I am…Really!” The importance of self-regulation in exercise contexts. Vol. 11, pp. 79-104. Personality and Individual Differences.

[6] Wilson, P. M. et al. 2004. Relationships between exercise regulations and motivational consequences in university students. March. Vol. 75, No. 1, pp. 81-91. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.