YOUR FITNESS BLOG

Dietary Self-Monitoring: The "Cornerstone" of Weight Loss

Dietary self-monitoring, which consists of recording all foods and beverages consumed along with portion sizes, is considered the “cornerstone” of weight loss treatment [1]. Self-monitoring has not received the rightful attention it deserves, and is typically viewed more as process that mediates weight loss, rather viewed as an important focus for weight loss intervention [5].

As negative energy balance is required for weight loss, recording key aspects of dietary intake allows an individual to monitor his or her progress towards achieving negative balance and facilitate adjustment made in eating. In a previous article, it was highlighted that individuals successful at maintaining weight loss over the long-term (i.e. at least one year), maintain heavy use of self-monitoring practices, which include tracking food intake.

The use of dietary self-monitoring has strong theoretical foundation [1, 2, 8]. Self-regulation, which is an umbrella term used to describe the various processes by which individuals pursue and achieve goals, suggests that self-monitoring precedes self-evaluation towards the desired goal and the information gained from self-monitoring is used to determine one’s goal progress [2, 8]. According to self-regulation theories, self-monitoring should lead to sustained efforts to match the behaviours (i.e. nutrition tracking) to the goals (i.e. weight loss) [1]. Within self-monitoring, recoding food intake is central within this process, involving deliberate attention to one’s eating and recording specific details of eating behaviour [2].

This article will review the important role of dietary self-monitoring in weight loss interventions and explore the research to understand which methods of dietary monitoring demonstrate the greatest efficacy, as well as identifying the frequency of self-monitoring required to achieve meaningful weight loss and factors that affect self-monitoring adherence.

Method of Dietary Self-Monitoring

A wide array of methods are used to perform dietary self-monitoring, including paper food diaries, meal photos, web-based food journalling, wearables, and mobile and tablet applications [11]. In the systematic review by Burke and colleagues (2011), over half the studies investigating the impact of dietary self-monitory on weight loss used paper diaries only [2, 5, 7]. In these studies, food monitoring varied from more general recordings of food eaten throughout each day, to more detailed recordings, including what time food was eaten, quality of food eaten, and grams of fat consumed [2, 5, 7]. In all studies, paper food diaries were associated with significant weight loss lending support to their use for effective self-monitoring [2, 5, 7].

The advent of nutritional digital applications like smartphone technologies (i.e. MyFitnessPal) have allowed for easier tabulation of daily calories, decreasing the burden of having to calculate calories manually and providing instant feedback on daily calorie consumption [6, 10, 11]. Having easy access to a database of foods, decreases the need to look up the nutritional values of foods and most nutritional applications allow for frequently consumed meals to be saved, therefore eliminating the hassle of repeated food searching and entry [6, 10, 11].

In support, research has shown a positive association between electronic self-mentoring and weight loss, with some studies demonstrating an advantage in digital food recording over paper diary form [4]. A two-year randomised clinical trial that compared dietary self-monitoring using either paper or electronic diary found that, compared to the paper diary, the electronic groups were more adherent to self-monitoring and these improvements in adherence led to a greater percent of weight loss [4]. Other studies have shows similar weight loss success between electronic and paper diary self-monitoring, however participants tended to report more convenience and social acceptance using electronic forms like smart phones applications [4, 6, 9, 10].

Frequency of Dietary Self-Monitoring

Research suggests that the accuracy and completeness of dietary self-monitoring are not as important as the frequency with which self-monitoring is performed [6, 9]. Even with app-based technology, daily recording of food intake is still perceived as effortful and can represent a significant time commitment [6]. Given that adherence to self-monitoring predicts weight loss success and self-monitoring overall tends to decline over time, it would be important to understand the threshold for dietary self-monitoring engagement needed to generate meaningful weight loss [6].

Ideally, dietary self-monitoring is continuous and updated, e.g. an individual records what he or she eats throughout the day. However, evidence shows that dietary self-monitoring is not always accurate and deteriorates over time [5]. Burke and colleagues (2008) found adherence to dietary self-monitoring declined in participants from 4.0 entries per day in the first 6 months, to 3.7 from months 6 to 12, then down to 2.2 entries per day from months 12 to 18 [5]. In their study, participants who exhibit less frequency of dietary recording were found to regain the most weight, consistent with other studies that looked at the impact of self-monitoring on weight loss [5].

Similar findings were published by Harvey and colleagues in 2019 [6]. In an effort to quantify the amount of time required and daily frequency of self-monitoring necessary for successful weight loss, the authors randomised obese individuals to an 18-month, online, group-based weight loss intervention [6]. In their study, participants were randomised to either Behavioural Therapy alone or Behavioural Therapy plus Motivational Interviewing [6]. Participants met once per week in closed groups for the first 6 months, then monthly for the remaining 12 months [6]. Participants were placed on a calorie-reduced diet and asked to self-monitor their daily food intake using online food journalling for the first 6 months [6]. Instructions were given to participants to record food intake throughout the day immediately after consumption and to check the balance of calories to meet their daily goal [6].

The authors found that among individuals losing ≥ 5% or ≥ 10% of their baseline weight, these individuals were spending approximately 23 to 24 minutes per day (2.5 hours per week) recording dietary intake durning the initial month of the program [6]. However, this time reduced to 15 to 16 minutes per day by month 6 [6]. Data from this study also suggest that recording food intake about 3x/day is associated with successful weight loss, compared with fewer dietary recording frequencies [6]. This means that participants would self-monitor closer to the time of consumption (i.e. breakfast, lunch, dinner), in contrast to recording daily food intake in a single sitting [6]. The implications of more frequent self-monitoring would be improved recording accuracy and thus a better understanding of total calories consumed throughout the day.

This study, as well as others, demonstrate that food journalling more times per day and more days in the month is significantly associated with greater weight loss [1, 6, 9]. However, with 34.5% of participants in this study not registering any food recordings by month 6, it should still remain the focus of weight loss interventions to identify strategies for sustaining higher frequencies of dietary self-monitoring over time [6].

Factors Affecting Dietary Self-Monitoring

Multiple factors are found to affect the efficacy of dietary self-monitoring. Increased consistency has been identified as a powerful factor with studies showing the most consistent self-monitors lose the most weight [1, 2, 9].

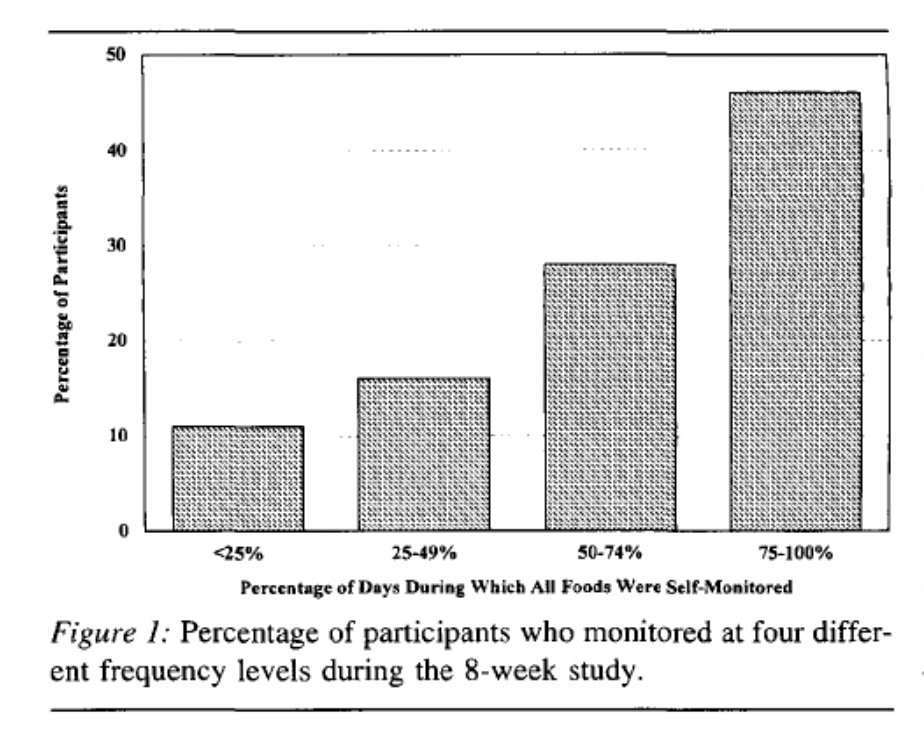

In support, Boutelle and colleagues (1998) found that increased self-monitoring consistency of food intake over an 8-week study significantly correlated with weight loss [1]. In their study, participants were asked to self-monitor daily food intake in booklets and researchers used a weekly rating scale to assess consistency [10]. Of the 59 individuals who participated in this study, 45.6% were found to monitor food intake on 75% or more of the days, while 10.5% of participants monitored food intake on fewer than 25% of the days [1]. By week 8, participants who demonstrated increased consistency with food monitoring more lost weight (mean weight change = -0.76kg) compared with less consistent self-monitors who actually regained weight (mean weight change = +0.48kg) [1].

The evidence would suggest that individuals with weight loss objectives must learn to observe their eating behaviour systematically and highly consistently. However, it still remains to be determined what causes certain individuals to sustain self-monitoring efforts? It is possible that individuals who sustain their self-monitoring efforts maintain better adaptive strategies to counteract barriers to adherence. Research has also suggested that individuals who had support from significant others (i.e. spouse) showed greater adherence with dietary self-monitoring [3]. Alternatively, these individuals may simply have higher motivations to self-monitor [3].

As previously discussed, evidence shows the more frequent individuals monitored their food intake, the more weight loss was achieved [5, 6, 9]. Similar to consistency, increased frequencies of dietary self-monitoring facilitates weight loss by helping individuals enhance their awareness of food consumed throughout the day and week, which in turn improves adherence to calorie intake goals [6, 9]. Paterson and colleagues (2014) showed that individuals who showed increased frequency of dietary self-monitoring, assess by total number of food diaries submitted, lost more weight when combined with more consistent food recording (i.e. number of weeks completing ≥ 3 records per week) [9]. In their study, subjects who were not consistent at least 50% of the time regained at least 5% of their body weight from 6-month assessment [9]. These findings reinforce the importance of identifying strategies that can enhance both frequency and consistency of dietary self-monitoring.

Practical Application

Dietary self-monitoring, the systematic observation in recording of eating behaviour, is shown to be a critical aspect of weight loss interventions [1]. A systematic review by Burke and colleagues published in the Journal of the American Dietetics Association showed that, among the fifteen studies that used dietary self-monitoring for weight loss, all of the studies had clinically significant weight loss outcomes [2].

Research shows that not just self-monitoring food intake, but highly consistent and frequent self-monitoring often correlates with significant weight loss and maintenance of weight control [6, 9]. Evidence has found that 23 to 24 minutes per day recording dietary intake may be required to generate meaningful weight loss (i.e. ≥ 5% or ≥ 10% weight loss), coupled with self-monitoring frequencies that aim to track each week, at least 3 or more times per day [6]. Aiming to self-monitor all foods eaten on at least 75% or more of the days are suggested to be a reasonable target for recording consistency [1].

Among all the varying methods for tracking food intake, using mobile, smart phone apps has been suggested to enhance adherence to dietary self-monitoring potentially more than other tools [4, 6, 11]. Automated calorie calculations, food nutrition value databases, enhanced convenience, more social acceptance, and instant feedback are all reasons why mobile devices can help increase the timeliness and accuracy of dietary self-monitoring to improve adherence [2, 11].

Notably, evidence shows that the detail of food records are not as relevant as the frequency and consistency of self-monitoring for weight loss [9, 11]. In fact, abbreviated methods that use simple checkboxes to estimate fat and calorie content of meals are found to be more effective for improving self-monitoring consistency compared with more detailed recordings [7]. Given this, focus should be placed on strategies to improve frequency and consistency of dietary self-monitoring, not necessarily the detail of recordings [7, 9].

For more information on our personal training services please click here to read more.

References:

[1] Boutelle, K. N. et al. 1998. Further Support for Consistent Self-Monitoring as a Vital Component of Successful Weight Control. May. Vol. 6, No. 3. pp.219-223. Obesity Research.

[2] Burke, L. E. et al. 2011. Self-Monitoring in Weight Loss: A Systematic Review of the Literature. January. Vol. 111, No. 1, pp.92-102. Journal of the American Dietetics Association.

[3] Burke, L. E. 2009. Experiences of Self-Monitoring: Narratives of Success and Struggle During Treatment for Obesity. June. Vol. 19, No.6, pp.815-828. Qualitative Health Research.

[4] Burke L. E. et al. 2009. Self-Monitoring in Behavioral Weight Loss Treatment: SMART Trial Short-term Results. Vol.17, S273. Obesity.

[5] Burke, L. E. et al. 2008. Using Instrumented Paper Diaries to Document Self-Monitoring Patterns in Weight-Loss. Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 182-193. Contemporary Clinical Trials.

[6] Harvey, J. et al. 2019. Log Often, Lose More: Electronic Dietary Self-Monitoring for Weight Loss. March. Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 380-384. Obesity.

[7] Helsel, D. L. et al. 2007. Comparison of Techniques for Self-Monitoring Eating and Exercise Behaviors on Weight Loss in a Correspondence-Based Intervention. October. Vol. 107, No. 10, pp.1807-1810. Journal of the American Dietetics Association.

[8] Mann, T. et al. 2013. Self-Regulation of Health Behavior: Social Psychological Approaches to Goal Setting and Goal Striving. Vol. 32, No. 5, pp.487-498. Health Psychology.

[9] Paterson, N. D. 2014. Dietary Self‐Monitoring and Long‐Term Success with Weight Management. September. Vol. 22, No. 9, pp.1962-1967. Obesity.

[10] Tate, D. F. 2001. Using Internet Technology to Deliver a Behavioral Weight Loss Program. March. Vol. 285, No. 9, pp.1172-1177. JAMA.

[11] Yu, Z. et al. 2015. Dietary Self-Monitoring in Weight Management: Current Evidence on Efficacy and Adherence. December. Vol. 115, No. 12, pp. 1931-1938. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.