YOUR FITNESS BLOG

How to Calculate Maintenance Calories

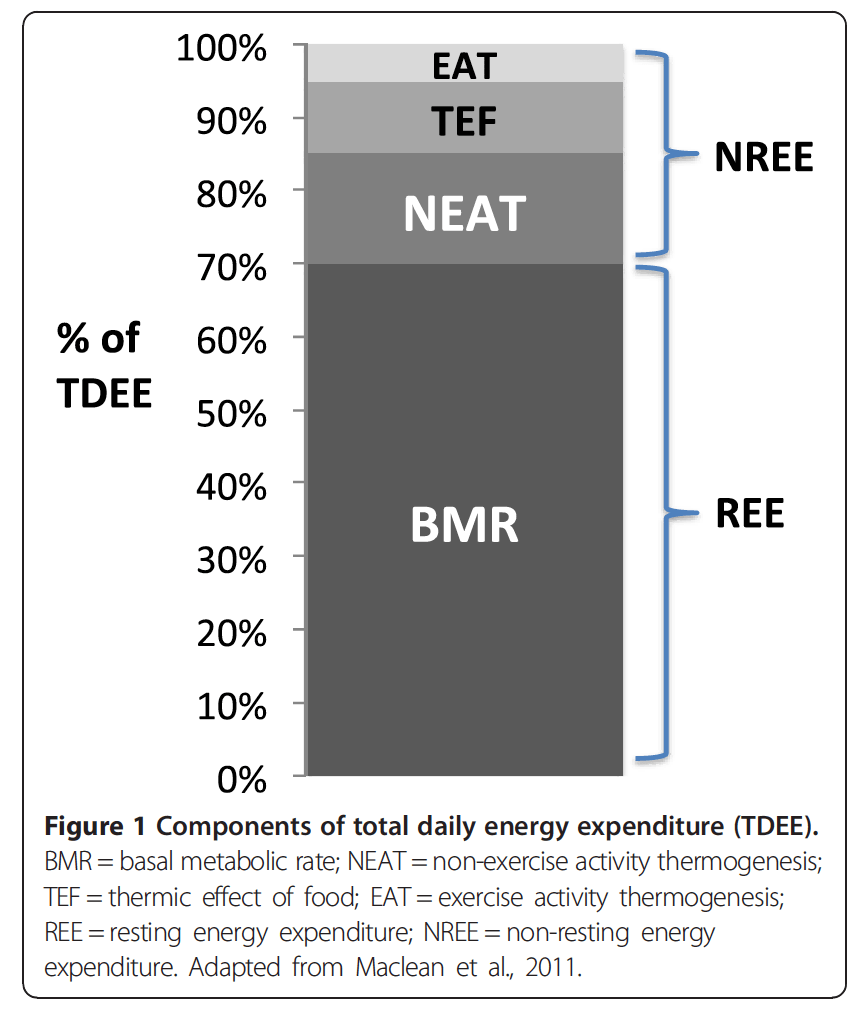

Our previous article discussed how to create an energy deficit for weight loss and how to adjust energy intake and/or expenditure to achieve continuous weight loss. This article will explain how to calculate maintenance calories, which can be used as a starting point from which to make nutritional adjustments when starting with a personal trainer (i.e. calorie deficit). Maintenance calories refers to the amount of calories required to maintain current weight [8]. There are four primary variables that influence maintenance calories and total daily energy expenditure (TDEE):

- Basal metabolic rate (BMR)

BMR is defined as the energy expended at complete rest and is measured in the lying position in the morning after sleep [2, 9]. BMR is the largest component of daily energy expenditure and is largely determined by the amount of fat-free mass (muscle) and to a lesser extent fat mass [6]. Therefore, an individual with more muscle or fat will have a higher BMR. In a sedentary lifestyle, BMR can represent as much as 70% of daily energy expenditure with individuals in sedentary occupations [1]. To differentiate, resting metabolic rate (RMR), is energy expended at rest, but at any point during the day [4]. RMR is generally within 10% of BMR [4].

- Thermic effect of food (TEF)

TEF is defined as the energy expended after eating. TEF generally represents about 10%-15% of total food intake [10]. Research shows a 6-7% increase in energy expenditure with carbohydrate meals, 3% increase with fats, and 25-40% energy increase with protein-based meals [10]. Therefore, those with diets higher in protein will expend significantly more from eating compared to fats or carbohydrates.

- Thermic effect of activity (TEA)

TEA refers to energy expended during formal activity (i.e. resistance exercise, cycling) and its value can vary greatly between chosen activity. TEA can represent 10-20% over BMR among more sedentary individuals (i.e. desk workers) and up to 100% over BMR for heavily active people [7].

- Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT)

NEAT is the energy expended during physical activity that excludes volitional-sporting-like exercise [5]. For example, fidgeting, walking and maintaining posture are all classified under NEAT [5]. NEAT represents approximately 15% of total daily energy expenditure and is found to vary considerably among people by up to 2000 calories/day with the greatest influence being occupation [3, 11].

Estimating Maintenance Calories

A number of different calculations, ranging from complex to simple, can be used to calculate maintenance calories. Importantly, any calculation should be accepted as purely an estimate and a starting point for understanding caloric needs.

Based on the caloric values yielded from BMR, TEF and TEA, Lyle Macdonald suggests a starting point of 14-16 calories per pound of body weight [7]. For example, an individual weighing 165 lbs (75kg) would yield a maintenance calorie value of 2,301-2,640 calories/day. Macdonald suggests that women, or those with slower metabolic rates, should use the lower value (14 cal/lb), while men, and individuals with faster metabolic rates, would apply the higher value (15 cal/lb) [7].

Alan Aragon provides a stepwise approach to calculating maintenance calories that takes into account both target body weight (TBW) and intensity of exercise [8]. Aragon defines TBW as a measure of lean muscle mass that also accounts for some variance [8]. Aragon’s method is described here:

The first step in how to calculate maintenance calories is determining TBW.

Step 1 – Calculate lean body mass (LBM)

A simple estimate of 25% of total body weight can be used to determine LBM. For example, an individual weighing 165 lbs would yield 41 lbs of fat mass and 124 lbs of lean mass (165 x .25 = 41 lbs). Alternatively, several online calculators are available that provide an estimate.

Step 2 – Determine target lean body mass and multiply this figure by 100

For example, an individual with 124 lbs of lean mass with the objective of gaining 2 lbs of lean muscle in 8 weeks would give a value of 12,600 (126 x 100 = 12,600).

Step 3 – Determine target body fat percentage and deducted this figure from 100

For example, an individual with 25% body fat with the objective of realistically losing 4-6% in 8 weeks would yield a value of 79 (100 – 21 = 79) to 81 (100 – 19 = 81).

Step 4 – Calculate TBW by dividing Step 2 by Step 3

For example, using the above figures, TBW for an 8 week period would be 159.5 lbs (12,600 / 79 = 159.5) to 155.5 lbs (12,600 / 81= 155.5).

Weekly training hours encompass any volitional type of activity [8]. For example, resistance training, running, cycling, hiking, swimming, etc. An individual that resistance trains twice a week for 60 minutes and cycles to work for 30 minutes, three times a week, would total 3.5 hours of weekly training.

Weekly intensity is graded from 9 to 11 and is described using the following criteria [8}:

9 = low intensity training

10 = moderate intensity training

11 = high intensity training

This figure is highly subjective and can be problematic under circumstances where intensity levels vary among weekly activities (i.e. strength training versus cycling). Once selected, weekly intensity is added to weekly training hours. For example, an individual with 3.5 hours of moderate weekly training would give a weekly training intensity of 13.5 (10 + 3.5 = 13.5).

To calculate maintenance calories, TBW is multiplied by weekly training intensity. For example, an individual with a TBW of 159.5 and weekly training intensity of 13.5 would yield 2,153 daily maintenance calories.

For individuals with a high metabolic rate or high NEAT, Aragon offers an additional formula:

TBW x (11 – 13 + Average Total Weekly Training Hours)

For example, an individual with a TBW of 159.5 that performs moderate intensity exercise (i.e. 60min), 3x/week and also has high NEAT would yield: 159.5 x (13 + 3) = 2,552 daily maintenance calories.

Adjusting Maintenance Calories

The reality of calorie calculations is that they may prove inaccurate. After obtaining an estimate of daily maintenance calories, it becomes more important to compare this estimation against actual fluctuations in weight. For example, if weight gain occurs under set maintenance calories, an adjustment should be made to lower caloric intake. In contrast, losing weight under maintenance calories would require an increase in daily caloric intake. Tracking maintenance calories against weight changes over the course of 2-4 weeks is advisable for understanding the accuracy of caloric estimation.

Summary

As a baseline from which to make nutritional adjustments, calculating maintenance calories can prove highly beneficial. For individuals with weight loss goals, determining maintenance calories is critical for setting an appropriate caloric deficit. Actual changes in body weight may contradict estimated caloric values, therefore one must anticipate having to modify caloric intake to achieve maintenance levels.

For more information on our personal training services please click here to read more.

References:

[1] Ferro-Luzzi, A. 2005. The conceptual framework for estimating food energy requirement. Public Health Nutrition. October. Vol. 8, No. 7A, pp. 940-952.

[2] Kelly, M. P. 2017. The American Council on Exercise (ACE). Resting Metabolic Rate: Best Ways to Measure It—And Raise It, Too [Online]. [viewed February 02, 2017]. Available from: https://www.acefitness.org/certifiednewsarticle/2882/resting-metabolic-rate-best-ways-to-measure-it-and/

[3] Levine, J. A. et al. 2006. Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis. The Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon of Societal Weight Gain. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. April. Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 729-736.

[4] Levine, J. A. 2004. Nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): environment and biology. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism. May. Vol. 285. No. 5. E675-685.

[5] Levine, J. A. et al. 1999. Role of Nonexercise Activity Thermogenesis in Resistance to Fat Gain in Humans. Science. January. Vol. 283, No. 5399, pp. 212-214.

[6] Johnstone, A. M. et al. 2005. Factors influencing variation in basal metabolic rate include fat-free mass, fat mass, age, and circulating thyroxine but not sex, circulating leptin, or triiodothyronine. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. November. Vol. 82, No. 5, pp. 941-948.

[7] Macdonald, L. 2008. Body Recomposition. How to Estimate Maintenance Calorie Intake – Q & A [Online]. [viewed February 02, 2017]. Available from: http://www.bodyrecomposition.com/fat-loss/how-to-estimate-maintenance-caloric-intake.html/.

[8] Schuler, L. & Aragon, A. 2014. The Lean Muscle Diet. How to Calculate Daily Calories. Rodale Inc. New York, NY.

[9] Sabounchi, N. S. et al. 2013. Best Fitting Prediction Equations for Basal Metabolic Rate: Informing Obesity Interventions in Diverse Populations. International Journal of Obesity (London). October. Vol. 37, No. 10, pp. 1364-1370.

[10] Scott, C. B. et al. 2007. Onset of the Thermic Effect of Feeding (TEF): a randomized cross-over trial. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. December. Vol. 4, No. 24. pp.

[11] Trexler, E. T. 2014. Metabolic Adaptations to Weight Loss Implications for the Athlete. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. February. Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 1186/1550-278.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.