YOUR FITNESS BLOG

4 Science-Backed Strategies for Accelerating Fat Loss

Introduction

Fat loss follows the principles of thermodynamics in that energy expenditure needs to be lower than energy intake for fat loss to occur. However, fat loss is clearly a result of a more complex set of biological, environmental and behavioural interactions, where changing any one of these factors can alter fat loss efforts [6]. For example, in the current obesogenic environment, the promotion of ultra-processed foods, like fast food and ready made meals, are ubiquitous [3].

It is also well established that a number of biological adaptations occur with energy restriction that activate the body’s self defence systems to resist fat loss [4]. These include a slowing of metabolic rate, decrease in spontaneous activity, and hormonal alterations that increase hunger and lower metabolic rate [4]. A primary outcome from neural adaptations in response to energy restriction is elevated hunger [4]. Overeating as a result of increased hunger (or decrease in satiation) can close the energy gap, further resisting fat loss.

Given the multiple factors that work against fat loss, identifying strategies that help create an energy deficit, increase satiety, and sustain fat lost over the long-term are highly relevant. This article will review four simple nutritional strategies that have been shown in the scientific literature to aid in fat loss efforts.

Fat Loss Strategy 1: Eat Less Ultra-Processed Foods

Ultra-processed foods like potato chips, fast food, cookies, brownies and commercial cereals and breads, are foods that go through a number of processes that add chemicals, colourings, sweeteners and preservatives [3]. These foods are typically inexpensive, convenient, and carry long shelf-lives [3]. Also, ultra-processed foods tend to be much higher in calorie-dense combinations of fat, protein, sugar, starch, and salt, compared to unprocessed or minimally process foods, which make them more palatable and preferred [2].

It is suggested that these very food properties are most likely to cause food cravings and loss of control of eating [2]. Just as the dogs in Ivan Pavlov’s famous 1890’s study learned to associate a bell ring with food and would salivate at the sound of a bell alone, it is suggested that our brains similarly learn to create sensory cues to ultra-processed foods that stimulate pleasure (via dopamine) and a higher motivation to eat them [2].

The reinforcing, motivating and palatable features of these ultra-processed foods are said to carry high “food reward,” an umbrella term used to describe how our brains value certain foods more than others and create more motivation to eat them [2]. If ultra-processed foods are higher in calories and their food properties make them highly motivating to eat, it becomes much more challenging to control caloric intake for fat loss under these conditions.

Reducing the amount of ultra-processed food and incorporating more unprocessed (i.e. fruits and vegetables) and minimally processed (i.e. potatoes, milk, grilled fish) foods in one’s nutrition can greatly help to minimise food reward and control calories consumed, making it easier to stay in a caloric deficit for fat loss.

Fat Loss Strategy 2: Eat More Low-Energy Dense Foods

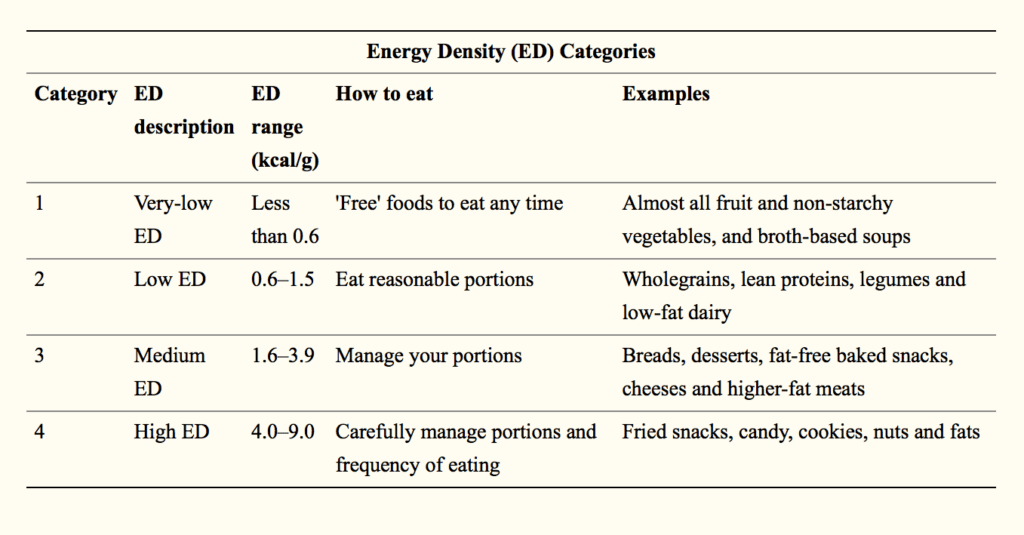

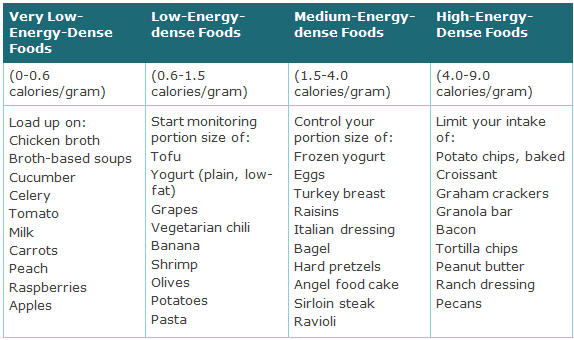

Energy density describes the energy content of a food (calories), divided by its weight (grams) [6]. For example, for a medium size apple that contains 80 calories and weighs 154 grams, its energy density is 0.5 (80/154 = 0.5). The energy density of foods can be divided into four categories as displayed below in Table 1 [8]. A food’s energy density depends both on its macronutrients (fats, proteins, carbohydrates) and its water content [7].

Taken from: Rolls, B. J. et al. 1988. The specificity of satiety: The influence of foods of different macronutrient content on the development of satiety. Physiology & Behaviour.

Research demonstrates that under ad libitum eating conditions (where people can eat as much as they want), people consistently eat more when given high energy dense foods compared with low energy dense foods [6]. Interestingly, when it comes to food intake, energy density appears to act independently of the amount of food consumed [7]. Rolls and colleagues (1998) demonstrated this when they fed subjects meals of varying energy densities (low, medium and high) [9]. In their study, they found that, over a two-day period, subjects in all three groups ate the same weight of food despite being provided with meals of different energy densities [9]. Activation of sensory nerves in the stomach that register food volume, not density, may explain why all three groups ate the same weight of food [9]. After the two days, the low calorie dense group ate approximately 400 calories per day less compared with the high calorie dense group [9]. With the low energy dense group consuming significantly fewer calories, fat loss would be more likely in this group over time compared with subjects in the high energy dense group.

Therefore, consuming foods lower in energy density, such as fruits and vegetables, lean proteins, legumes, and low-fat dairy, can help greatly reduce calorie intake, thereby facilitating fat loss efforts.

Fat Loss Strategy 3: Eat More High Fibre Foods

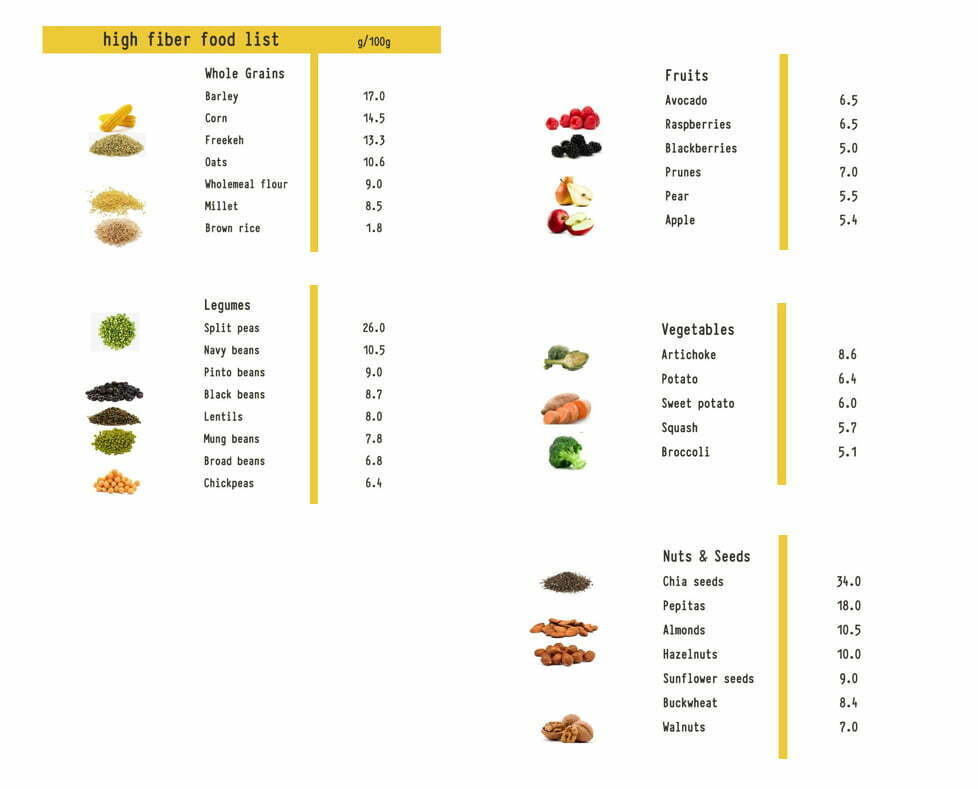

Fibre are complex carbohydrates that pass through the small intestine undigested and enter the large intestine [12]. In general, there are two main types of fibre: soluble and insoluble fibre [12]. Because high fibre foods are primarily made up of water, they typically supply fewer calories and have lower energy densities compared with low fibre foods [7]. For example, only 9 potato chips (Lay’s Classic) provide 100 calories, whereas, for the same amount of calories, this would equate to 3 cups of popcorn. For fat loss, this means that larger amounts (greater volume) of popcorn can be consumed at relatively lower calorie content.

Nutritional scientist Barbara Rolls explains that consuming greater food volume can limit food intake via sensory specific satiety, which describes a decline in the pleasure response to the sensory properties of food as it is consumed [7]. In other words, as more of a particular food is consumed, the satisfaction of this food decreases, resulting in a desire to limit eating. Given this, consuming greater amounts of popcorn, as opposed to potato chips, can help to activate sensory specific satiety because of the relatively larger volumes that can be consumed, at far less calories.

Also, other physical and chemical characteristics of dietary fibre make it highly relevant to fat loss. Dietary fibre has water-holding capacity, bulking and viscous properties that are shown to slow digestion and contribute to gastric (stomach) distention, which contribute to feelings of satiety and is shown to decrease food intake [12]. Mechanistically, gastric distention may help improve satiety by activating sensory receptors in the stomach that communicate feelings of fullness to the brain [7].

Eating more high fibre foods like different fruits, vegetables, whole grains and legumes can help to enhance satiety, making it easier to limit food intake as well as allowing for greater volumes of these fibrous foods to be consumed with the benefit of reduced calorie intake.

Fat Loss Strategy 4: Increase Daily Protein Intake

Dietary protein is a macronutrient found in animal and plant-based foods, and alternative sources such as algae, bacteria and fungi [11]. Although higher protein intakes are generally associated with maximising muscle development, research demonstrates that high protein diets, where protein represents 25% of more of total calories, can be effective for fat loss [5]. One potential mechanism for how protein facilitates fat loss is through diet-induced thermogenesis [5]. Thermic effect of food is defined as the increase in energy expenditure above baseline following consumption due to energy requirements for the digestion, absorption, and disposal of nutrients [5].

Protein is found to have a thermic effect of 20-35% of energy consumed [5]. A study by Eistenstein and colleagues (2002) found that for a 2,000 calorie diet, increasing protein intake from 15% to 30% led to an energy expenditure increase of 22 calories per day due to thermic effect [1]. Other studies have shown increases of up to 90 calories per day from higher protein intakes [5]. Although this figure may appear relatively small, consumption over a longer period could become significant for helping fat loss, particularly when combined with other strategies.

Also, a number of studies demonstrate the potential satiating effects of high protein diets, which, similar to high fibre foods, may have beneficial effects on limiting energy intake for fat loss [5]. Rolls and colleagues (1988) performed a study that provided five calorically matched preload meals (high protein (75% protein), high fat, high starch, high sucrose, and mixed preloads) to 10 females subjects on separate occasions, following which, subjects were asked to their rate feelings of hunger and satiety [10]. Two hours following preload meals, subjects who received the high protein and high starch meals reported the lowest hunger and highest satiety ratings compared to the other preload meals, lending support to the potential satiating effect of higher protein intake [10]

A potential mechanism to explain why higher protein intakes may enhance satiety is via changes in appetite hormones like appetite stimulating hormone ghrelin and satiety hormones GLP-1 and peptide YY [11]. It is suggested that protein-induced satiety is concomitant with a decrease in ghrelin and increase in both GLP-1 and peptide YY [11].

Increasing protein intake to represent at least 25% or more of total calories or 1.2-1.6 grams per kilogram can facilitate fat loss via increase thermic effect, while providing enhanced satiety along with high fibre foods.

Summary

Under the first law of thermodynamics, calorie intake is required to be lower than calorie output for fat loss to occur. On the surface, creating an energy deficit can appear simple. However, biological, environmental and behavioural pressures make fat loss significantly more challenging. Simple nutritional strategies that limit consumption of ultra-processed foods, while increasing consumption of low energy dense, high fibre foods, and increasing daily protein intake, have strong theoretical and clinical support for helping to facilitate fat loss efforts.

For more information on our personal training services please click here to read more.

References:

[1] Eistenstein, J. et al. 2002. High-protein Weight-loss Diets: Are They Safe and Do They Work? a Review of the Experimental and Epidemiologic Data. July. Vol. 60, No. 7, pp.189-200. Nutrition Reviews.

[2] Guyenet, S. 2017. The Hungry Brain. Vermillion: London.

[3] Hall, K. D., et al. 2019. Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. July. Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 67-77. Cell Metabolism.

[4] Hall, K. D. 2018. Metabolic Adaptations to Weight Loss. May. Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 790-791. Obesity.

[5] Halton, T. L. and Frank, H, B. The Effects of High Protein Diets on Thermogenesis, Satiety and Weight Loss: A Critical Review. October. Vol. 23, No. 5, pp.373-385. Journal of the American College of Nutrition.

[6] MacLean, P. S. et al. 2011. Biology’s Response to Dieting: The Impetus for Weight Regain. September, Vol. 301, No. 3. American Journal of Physiology Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology.

[6] Poppitt, S. D. and Prentice, A. M. 1996. Energy Density and Its Role in the Control of Food Intake: Evidence From Metabolic and Community Studies. April. Vol. 26, No. 2, pp.153-174. Appetite.

[7] Rolls, B. J. 2017. Dietary Energy Density: Applying Behavioural Science to Weight Managements. September. Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 246-253. Nutrition Bulletin.

[8] Rolls, B. J. 2012. The Ultimate Volumetrics Diet. William Morrow: New York.

[9] Rolls, B. J. et al. 1996. Energy Density of Foods Affects Energy Intake in Normal-weight Women. April. Vol. 67, No. 3, pp. 412-420. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

[10] Rolls, B. J. et al. 1988. The specificity of satiety: The influence of foods of different macronutrient content on the development of satiety. Vol. 43, No. 2, pp.145-153. Physiology & Behaviour.

[11] Wang, S. and Wang, C. 2019 The Effect of Dietary Protein on Weight Loss, Satiety and Appetite Hormone. February. Vol. 3, No. 2. ACTA Scientific Nutritional Health.

[12] Williams, B. A., et al. 2019. “Dietary Fibre”: Moving Beyond the “Soluble/Insoluble” Classification for Monogastric Nutrition, with an Emphasis on Humans and Pigs. May. Vol. 10, No. 45. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.