YOUR FITNESS BLOG

3 Ways Your Food Environment Promotes Weight Gain

Introduction

The food environment is a heavily under appreciated factor when it come to managing weight gain and refers to factors directly related to a way food is presented or delivered, such as its visibility, proximity, structure, packaging, portion size, or how it is served [10]. While people tend to acknowledge that environmental factors influence weight gain, they often wrongly believe they are unaffected. People are also often surprised at how much food they consume, which implies they may lack important consumption awareness or fail to effectively self-monitor food intake [10}.

For many individuals with weight loss objectives, self-monitoring (tracking) of food intake can be an inconvenience and annoyance. Instead, people tend to rely on adjusting off consumption norms to determine appropriate food intake [10]. That is, how much one normally consumes [10]. The issue is that food consumption is greatly influenced by alternative norms and environmental cues, such as food proximity, variety, or portion size [8]. For example, large plate sizes may suggest, at least perceptionally, that it is appropriate to consume more food that smaller plate sizes [10]. Without food monitoring, the impact of environmental factors, such as plate size, on food consumption is magnified because they can easily distort one’s estimate of how much is eaten [8].

Research shows that people eat more of a food when that food closer to them, a concept referred to as “proximity effect,” as well as when food is available in abundance and more visible [5. 9]. This suggests that the convenience and salience of foods can play an important roll in consumption frequency and ultimately influence weight gain. The question is then how can someone with weight loss objectives modify his or her food environment to reduce or eliminate the unintended effects on consumption? This article will identify three environmental traps within food salience, variety, and portion sizing that facilitate over food consumption and outline practical-based strategies within each area to alter the food environment to help control consumption.

Salient Food Promotes Weight Gain

The visual cue of seeing a food can be a powerful stimulant for unintended overconsumption and weight gain. Research demonstrates that higher food visibility of favourable foods can increase hunger and stimulate salivation, which can then result in greater food consumption [9, 10]. In support, Wansink and colleagues (2006) found that people consumed sweets 46% more quickly when the sweets were placed in clear containers, making them more visible, compared to when placed in opaque containers [9].

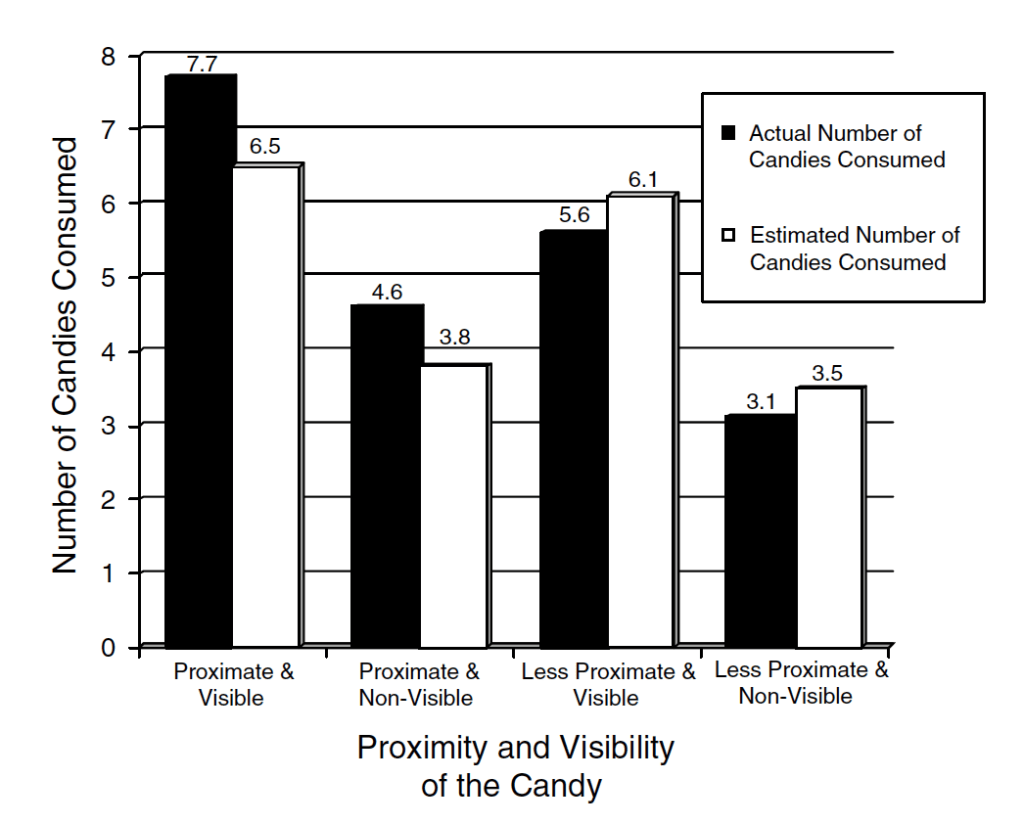

In their study, the authors tested the influence on the visibility and proximity of chocolates on 40 female office workers [9]. The conditions tested included placing a bowl of chocolates (Hershey Kiss’s) on the desk of the participants in either covered bowls or opaque bowls [9]. The authors also tested proximity by manipulated the positioning the bowls, where the bowls were either positioned on the desk of participants, or 2 meters away from their desks [9]. After a 4-week study period, the authors found that participants ate more than double the amount of chocolates when the chocolates were placed on the desk and in a clear bowl, compared to when the chocolates were placed 2 meters away in an opaque bowl [9].

Interestingly, when participants were asked to estimate how many chocolates they believed they ate, participants tended to underestimate how many chocolates they ate when the candies were most proximate (i.e. positioned on the desk) and overestimate how many they ate when less proximate (i.e. 2 meters away) [9]. These findings confirm the idea that people can lack consumption awareness under situations of strong visual food cues and underreport food eaten when favourable food is visible and in close proximity [9]. When asked to rate the influence of visibility and proximity, participants rated the candies as “more difficult to resist” and “attracting more attention” when the chocolates were more visible (i.e. in clear bowls), as well as when the chocolates were more proximal [9].

Although cognitive-based mechanisms can be used to explain why visible foods increase temptation for consumption, physiological components that can enhance hunger are also heavily involved [10]. Neuroscientist and obesity researcher, Stephan Guyenet, highlights that the visibility and smell of favourable foods enhance hunger and cravings by increasing the release of dopamine in the brain, a neurotransmitter involved in pleasure and learning [3]. Guyenet indicates that the sight and smell of favourable, calorie-rich foods stimulates a high motivation to eat them, or what is described as high “food reward” [3]. The process of learning to associate the sight and smell of foods, with the help of dopamine, makes these sensory cues very challenging to override [3].

Practical-Based Strategies

At home, or work environment, remove all tempting, high calorie-dense foods to eliminate exposure to food cues. These include common confectionery snacks like cookies, crisps, and sweets, but also “healthier” food items like salted nuts. If your family members consume these foods, you need to re-position them in inconvenient places in the house. For example, moving snacks from the kitchen counter to the highest shelf in the cupboard where they are completely out of sight and difficult to reach. Alternatively, moving snacks to inconvenient locations in the house that require more effort to obtain. By eliminating powerful visual cues to consume these foods, you will reduce your cravings.

As you eliminate powerful visual cues to high calorie-dense foods, also reduce barriers to consuming foods that you want to eat more of. For example, just the effort of peeling an orange or pineapple, can become a barrier for consumption. Instead, already have these foods prepared (ii.e. fruit peeled and sliced), ready to eat, and highly visible places (i.e. eye level in fridge). The objective is to re-design your food environment to make more visible and easily accessible the food you need to eat more of, while doing the opposite for foods you need reduce consumption (you can still have them occasionally).

More Food Variety Promotes Weight Gain

A number of research studies demonstrate that simply increasing the variety of foods can increase its consumption and lead to weight gain. A phenomenon researchers call the “buffet effect,” because of the overconsumption that is known to occur at buffets, increased food variety can increase consumption because it exposes the brain to new sensory stimuluses that consequently increase food reward and motivation to eat [3]. It is suggested that food variety relates to habituation [3]. Habituation refers to the response where, the more we are exposed to particular stimulus, the less we respond to it and has been demonstrated in the context of food [3].

Research by Rolls and colleagues (1981) found that when subjects were asked to rate the palatability of provided foods, their palatability ratings of a particular food decreased if they were given that same food shortly after [6]. In that study, volunteers were asked to rate the palatability of eight different foods by tasting a small amount of each food [6]. Then, participants were given one of the eight food items again for lunch [6]. The authors found that the palatability rating of foods decreased more in the foods that were eaten previously compared to the other foods that were not [6]. Furthermore, when participants were given a second course containing all eight of the same foods they were given for lunch, they ate less [6]. This suggests habituation to certain foods in the study lowered the appeal to eat them, a term Rolls coined as “sensory-specific satiety [6].”

Habituation can also explain the “buffet effect.” At a buffet, wide food variety allows us to select from different foods that all have different sensory properties (i.e. sweet, sour, fatty, salty) from each other [3]. Given this, the brain does not habituate to any particular food and can experience a new sensory experience with each food variety [3]. An individual may feel “full” or satiated after eating a large savoury meal, yet still desire a sweet dessert because it provides a novel stimulus [3]. This is how, with greater food variety, it is common for people to overeat.

Practical-Based Strategies

“Sensory-specific satiety” is a sensation of fullness applied to foods of similar sensory properties (i.e. sweet, salty, fatty) as to the one’s just eaten [7[. To apply this phenomenon, select a food of similar property to your “trigger” food. For example, eat two or more sweet tasting fruits prior to having dessert. With similar sweet properties, the fruits will stimulate sensory-specific satiety and help to manage dessert cravings. When it comes to high-calorie dense foods, limit the variety of these foods to naturally promote habituation. Stick to one or two varieties only of a particular food and you will find it will better manage overconsumption.

Large Portion Sizes Promotes Weight Gain

Larger food portions sizes have been studied extensively and consistently show significant increase in calorie intake and potential for greater weight gain. A meta-analytic review by Zlatevska and colleagues (2014) showed that doubling a food portion size leads to about a 35% increase in calorie intake [11]. Furthermore, in a 2015 Cochrane review by Hollands and colleagues, the authors found that calories from food and non-alcoholic beverages attributable to differences in portions sizes fell between 215 and 275 calories per day [4].

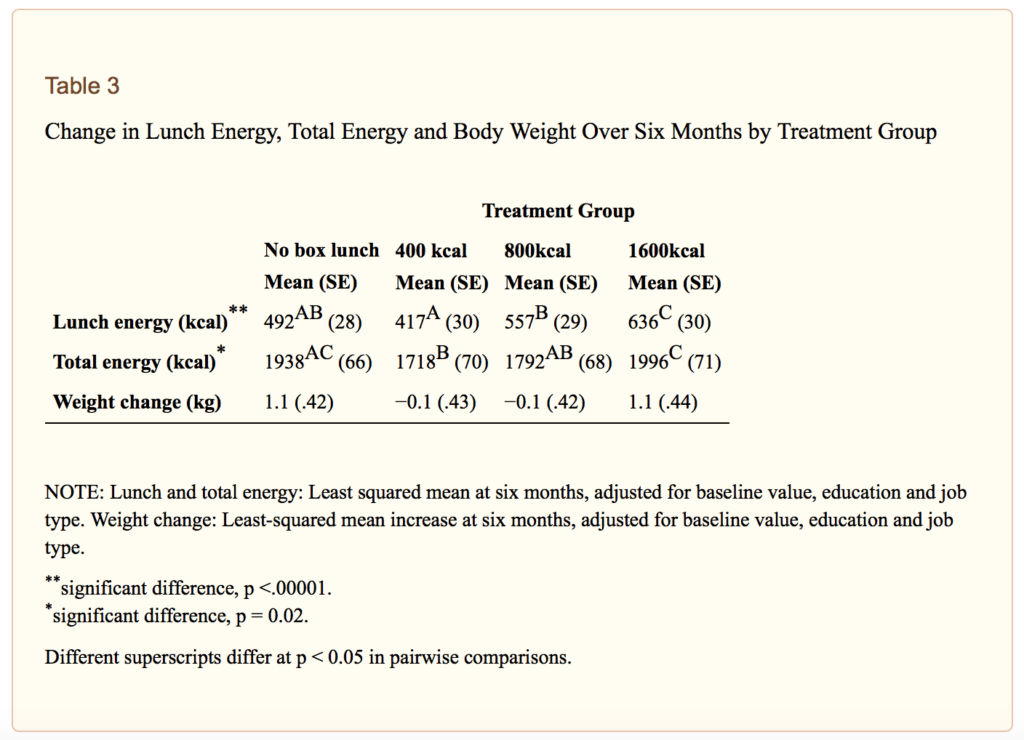

A study published by French and colleagues (2014) in the Journal of Obesity showed larger lunch portion sizes led to a significant increase in calorie intake and weight gain over 6 months in a real-life, work setting [2]. In their study, the authors randomly assigned participants to receive either a low portion size (400 calories), moderate portion size (800 calories), or high portion size (1,600 calories) lunch boxes for 6 months [2]. The study consisted of manipulating lunch menus with specific energy content according to each experimental condition [2]. Bodyweight and energy intake of participants were measured at 1, 3, and 6-months [1].

The authors found that participants in the large box lunch group consumed significantly more calories compared to the low and moderate box lunch groups, which persisted up to the 6 months [2]. Also, the high portion size group experienced significant weight gain over the study period, while there was no change in bodyweight with the low and moderate box lunch groups from baseline to 6-months [2].

Although many mechanisms have been used to explain this “portion-size effect,” a primary explantation as to why larger portion sizes stimulate overeating is that they create new consumption norms or level of food “appropriateness [8].” As previously indicated, consumption norms refer to how much food an individual “normally” consumes or deems “appropriate [#].” Within the potion-size effect concept, as opposed to hunger or satiety guiding intake, food portion size dictates the amount consumed and serves as the food norm [10]. With larger portion sizes, they implicitly suggest what is “normal” to an individual [10].

Practical-Based Strategies

Manage your food portions by buying smaller portions of the foods you tend to over-consume. Avoid buying calorie-dense foods in large portion / package sizes (i.e tubs of ice cream, large bags of crisps, bags of chocolate). Instead, purchase only individual portion sizes. For example, an individual bar of chocolate instead of a packet or box, or an individual serving of ice cream or crips instead of a tub or large bag. Also, use smaller dishes (i.e. plates and bowls) when plating higher calorie foods. For example, using a large plate with pasta will naturally encourage larger portions and tend to lead to overconsumption. Whereas, using a smaller plate will encourage more reasonable size portioning, even if you have a second serving of the pasta.

Summary

While much of the focus in weight loss is on food choice, food consumption plays a more important role in managing weight gain. Food choice decisions determines what we eat (i.e. pasta, pizza, soup, salad), while food consumption decisions determines how much we eat (i.e. two plates of pasta, tub of ice cream). As it is generally accepted that any food can fit into a healthy diet, it is more the overconsumption of foods, even those considered “healthy foods,” that lead to weight gain.

The food environment, which relates to the way food is presented, has significant impact over food consumption. Total food consumption, which includes how often a food is eaten (frequency) and how much is eaten at a time (volume), are greatly influenced by the food environment. The frequency of food consumed is heavily influenced by salience (visibility and smell) and the ease or effort required to locate and eat the food. The volume of foods is mediated by an one’s consumption norm, which is influenced by food variety and portion sizing. Learning how food environment factors such as these influence consumption and how one can alter his or her food environment to help reduce consumption are both critical for managing short and long-term weight gain.

For more information on our personal training services please click here to read more.

References:

[1] Chandon, P. and Wansink, B. 2002. Does Stockpiling Accelerate Consumption. A Convenience-Salience Framework of Consumption Stockpiling. Vol. 39, pp.321–335. Journal of Marketing Research.

[2] French, S. A. et al. 2014. Portion Size Effects on Weight Gain in a Free Living Setting. June. Vol. 22. No. 6. pp. 1400-1405. Obesity.

[3] Guyenet, J. S. 2017. The Hungry Brain. Vermillion: London.

[4] Hollands, G. J. et al. 2015. Portion, Package or Tableware Size for Changing Selection and Consumption of Food, Alcohol and Tobacco. September.. Vol. 9. Cochrane Database Systematic Review.

[5] Hunter, J. A. et al. 2016. Impact of Altering Proximity on Snack Food Intake in Individuals with High and Low Executive Function: Study Protocol. June. Vol 16. p. 504. BMC Public Health.

[6] Rolls, B. J. et al. 1981. Variety In A Meal Enhances Food Intake In Man. February. Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 215-221. Physiology & Behaviour.

[7] Rolls, B. J. et al. 1988. The specificity of satiety: The influence of foods of different macronutrient content on the development of satiety. Vol. 43, No. 2, pp.145-153. Physiology & Behaviour.

[8] Steenhuis, I. & Poelman, M. 2017. Portion Size: Latest Developments and Interventions. March. Vo. 6, No. 1, pp. 10-17. Current Obesity Reports.

[9] Wansink, B. 2016. The Office Candy Dish: Proximity’s Influence on Estimated and Actual Consumption. May. Vo. 30, No. 5, pp. 871-875. International Journal of Obesity.

[10] Wansink, B. 2004. Environmental Factors that Increase the Food Intake and Consumption Volume of Unknowing Consumers. Vol. 24, pp. 455-479. Annual Review of Nutrition.

[11] Zlatevska, N. et al. 2014. Sizing Up the Effect of Portion Size on Consumption: A Meta-Analytic Review. May. Vol. 78, No. 3, pp. 140–154. Journal of Marketing.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.