YOUR FITNESS BLOG

Gluten's Dark Side!

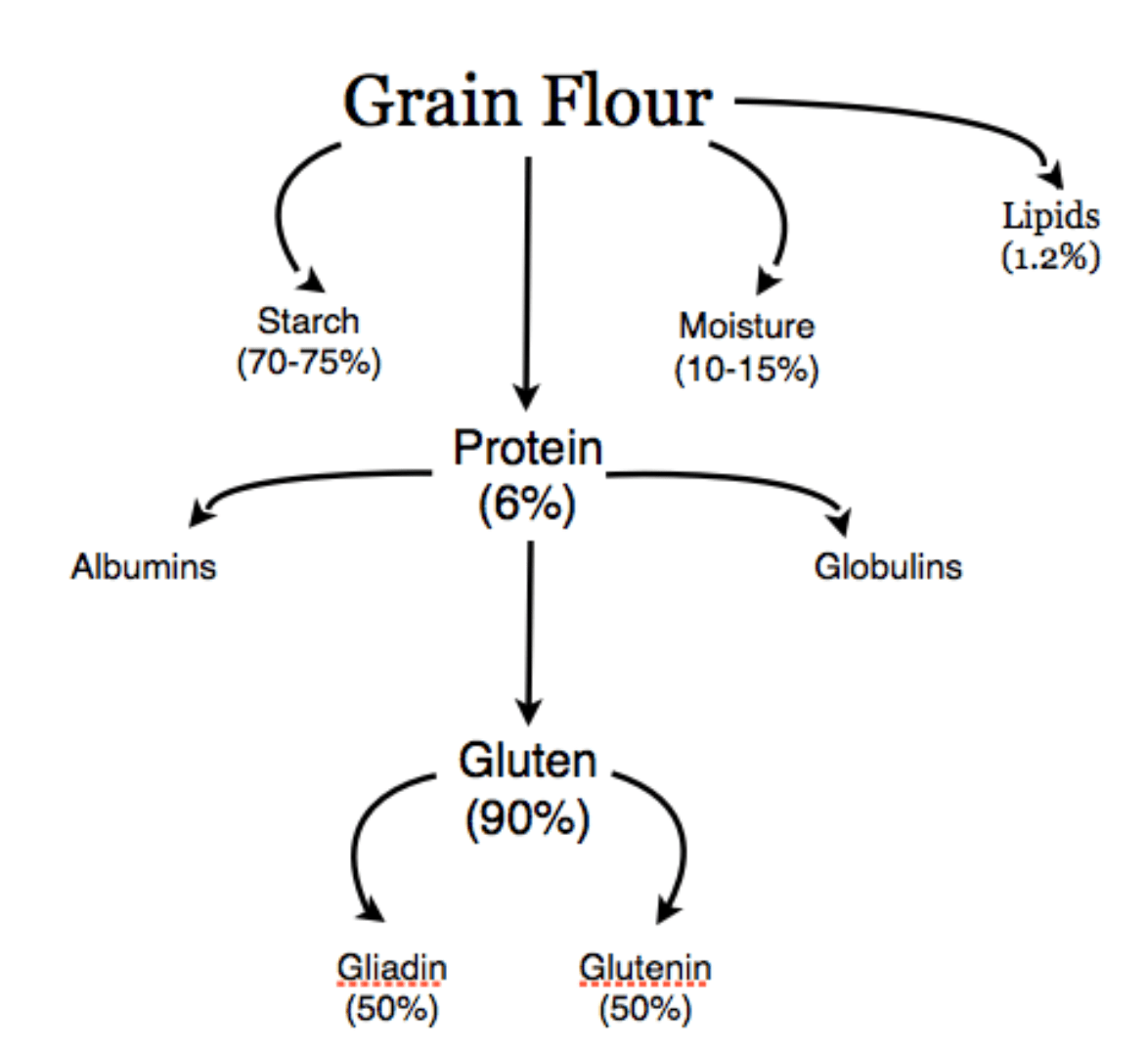

Gluten can be defined as “the rubbery mass that remains when wheat dough is washed in water to remove starch granules and water soluble constituents” [8, 11]. Alternatively, in the context of gluten sensitivity, gluten can be defined as “a protein fraction from wheat, rye, barley, oats or their crossbred varieties and derivatives, to which some persons are intolerant and that is insoluble in water and 0.5 mol/L NaCl” [8].

Gluten is generally divided into protein fractions according to their solubility: alcohol-insoluble “glutenins” and alcohol-soluble “gliadin” proteins [4, 11]. Both proteins make important contributions to making dough. Gliadins contribute mainly to the viscosity and extensibility of dough, while glutenins are responsible for the strength and elasticity in dough [11].

Historical Perspective

Archaeological and geological evaluation of pre-agricultural populations shows that human consumption of gluten-containing grains only occurred about 11,000 years ago with the advent of agriculture and prior to this time period, there was no evidence of regular grain consumption [3]. Furthermore, anthropological reports show traditional, pre-agricultural populations generally lived free of chronic degenerative diseases like obesity, type II diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease, which have now risen to epidemic proportions [3]. Importantly, 11,000 years marks only 0.5% of human history, simply not long for the human digestive system to have evolved to break down gluten proteins [3].

The agricultural and industrial era represented an evolutionary challenge for humans with widespread production and consumption of refined cereal grains, which created conditions for human disease. These conditions have further led to a global increase in gluten exposure and gluten reactions like wheat allergies (WA), celiac disease (CD), and non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS).

Wheat Allergies (WA)

What is a Wheat Allergy?

A wheat allergy is an adverse immune reaction to one or more of the proteins found in wheat [7]. WA can be classified into an (1) immediate food allergy, (2) wheat-dependent exercise induced anaphylaxis, (3) respiratory allergy, or (4) contact urticaria (hives) [7].

How Common are Wheat Allergies?

Zuidmeer and colleagues (2008) performed a systematic review of population-based studies from the UK and Germany and reported positive WA among children, with a prevalence as high as 0.5% [13]. Among adults, the prevalence of WA (assessed by IgE) was higher (> 3% in several studies) [13]. Multiple studies report that WA represents about 11% to 25% of the entire food allergy population [8].

Symptoms of Wheat Allergies

Symptoms of WA are similar to those of other classic food allergies, which include skin (e.g. swelling, itching, hives), respiratory (e.g. wheezing, impaired breathing, bronchial obstruction) and gastrointestinal (e.g., bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhoea) [6]. Also, anaphylaxis symptoms has been linked to WA [6].

Mechanisms Behind Wheat Allergies

Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies play an important part in the onset of WA. IgE antibodies function to bind to invaders (antigens), which create an inflammatory response intended to rid the body of infection or render the antigen inactive [1]. While IgE antibodies may combat the antigen, they also cause the release of histamines and other chemicals into the bloodstream that cause allergy symptoms like sneezing or abdominal pain [1].

The allergic response from the ingestion of wheat is caused by an immune reaction to the specific grain protein named gliadins [7]. In the case of respiratory allergies from wheat exposure, a group of wheat proteins called ?-amylase inhibitors are strongly associated with this response in addition to other proteins present in wheat like germ agglutinin and non-specific lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) [7].

Why Do Wheat Allergies Occur?

There is no single cause for the development of WA. A specific class of antibodies known as secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA), which help the gut to develop by enhancing intestinal barrier function, may increase the risk of WA if insufficient [1].

Also, immaturity of the intestinal barrier or digestive tract in addition to inadequate cultivation of healthy bacteria at birth can increase the risk of WA [1]. Even the absence of breast milk can increase the development of WA, as antibodies to gluten peptides from wheat are available in breast milk and breastfeeding has been shown to reduce gluten-triggered disorders in children [1].

Moreover, family history can play an important role in WA [1]. Children, who have a genetic predisposition to produce excess IgE, caused by the mother suffering from various allergies, are at least 8 times more likely to develop WA when delivered by caesarean section [1].

Celiac Disease (CD)

What is Celiac Disease?

Celiac Disease is an autoimmune condition (whereby the body’s immune system attacks its own healthy cells) triggered by the intake of gluten-containing wheat, rye and barley [8, 9].

How Common is Celiac Disease?

In the UK, there has been a 4-fold increase (9,087 cases) of CD between 1990 and 2011 [9]. Among children in Scotland, there has been a dramatic 6.4 fold increase (266 biopsy-positive children) in CD between 1990 and 2009 and similar trends have been reported in Europe and North America [10]. Also, CD is more common among females than males with a suggested ratio of 2:1 [8].

Symptoms of Celiac Disease

Symptoms of CD can present as classical intestinal features including different gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhoea, abdominal pain and weight loss or non-classical extra-intestinal features like osteoporosis, anemia and neurological disturbances [7]

Mechanisms Behind Celiac Disease

When gluten-containing foods are ingested, the proteins in gluten are only partially broken down during digestion because of their high content of glutamine and proline residues [6]. Peptides (a molecule consisting of 2 or more amino acids) are then accumulated in the tubular opening in the intestines (intestinal lumen) and are responsible for an immune response characteristic of CD [6].

On exposure to gluten, inflammation is induced in the tissues that line the small intestine (mucosa), which leads to wasting of the villi (finger-like projects that line the small intestine) [5]. This disruption to the villi results in damage to the tight junction of cells that function like a wall protecting the internal tissues from environmental stresses, bacterial infection, and chemical damage [5]. Compromise to the tight junctions that form this protective intestinal barrier lead to an immune response and trigger CD symptoms [2].

Why Does Celiac Disease Occur?

Genetic predisposition plays an important role in CD as it is well established that CD is associated with specific genes called human leukocyte antigen (HLA) (HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8) [ 5,7]. Carriers of the HLA genes account for about 40% of the genetic risk for CD [5]. However, it has been shown that only a small percentage of those that carry the HLA gene actually have CD [5]. Therefore, other factors must be involved in the onset of CD.

It has been suggested that imbalances in intestinal microorganisms (microbiota) may contribute to manifestations of CD [5]. Research shows that individuals with CD present with an imbalance of healthy bacteria in the small intestine with increased abundance of the bacteria called Bacteroides and a decreased in the bacteria called Bifidobacterium [5]. Even the initial development of the gastrointestinal tract in infants plays an important role in the microbiota and immune response later in life as an adult [5]. It has been demonstrated that events during infancy that may cause disturbances in gut microbiota such as infection and antibiotic treatment have been associated with CD in infants that are genetically susceptible [5].

Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS)

What is Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity?

NCGS is a gluten (wheat) dependent disorder where neither allergic nor autoimmune mechanisms are involved [7]. In the literature, alternative names have been used to describe NCGS like gluten sensitivity, gluten hypersensitivity, or non-celiac gluten intolerance [2]. NCGS is distinct from CD in that it is not accompanied by anti-tissue transglutaminase 2 (anti-TG2) antibodies, which are proteins that defend against harmful substances in the body like bacteria or viruses [7, 8]. These anti-TGS antibodies are present in the small intestine in CD patients, but not in those with NCGS [8].

How Common is Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity?

Estimating the prevalence of NCGS is not accurately possible as many are self-diagnosed in addition to the lack of objective diagnostic criteria for NCGS assessment [4]. As a result, various estimates ranging broadly from 0.6% to around 6% to an alarming 63% of the general population have been made [2, 4]. NCGS appears to be more common in females and in young/middle age adults (17-63 years age range) [2, 4].

Symptoms of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Symptoms of NCGS include irritable bowl (IBS)-like symptoms including abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea and/or constipation, nausea, and flatulence [2, 4]. Symptoms outside the intestinal tract include headaches, joint and muscle pain, muscle contractions, leg or arm numbness, excessive tiredness, “foggy mind”, weight loss and anaemia [2, 4]. Also, symptoms can manifest themselves as behavioral disturbances like disturbances in attention and depression [2].

Mechanisms Behind Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Unlike patients with CD, research shows individuals with NCGS do not react adversely to the protein gliadin present in gluten [2]. Some studies suggest that a family of non-gluten proteins present in wheat called wheat amylase trypsin inhibitors (ATIs) may be responsible for NCGS [2, 12]. ATI proteins function to naturally protect wheat from pests [12]. And, as ATI content has dramatically increased in recent years to make wheat more pest-resistant, ATI content has similarly increases [12]. It is possible then, that an increase in ATIs might explain the growing number of NCGS [12].

Although, ATIs may not be the only cause of NCGS [2, 12]. Short-chain carbohydrates known as FODMAPs (fermented oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) cause symptoms of NCGS, but not through an immune response as with ATIs. Rather, FODMAPs cause symptoms through the indigestible nature of these carbohydrates that cause water retention and gas production in the small intestine [12].

Why Does Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Occur?

Only 50% of people with NCGS have the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) (HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8) genes, which are strong diagnostic markers in those with CD [2]. Therefore, as no adaptive immunity markers are present in NCGS, etiology is unknown [5]. However, it is clear that NCGS involves innate immune mechanisms. The innate immune system functions to respond quickly to certain general signs of infection [6, 12]. Cells of the innate immune system have receptors called Toll Like Receptors (TLRs) that sense and defend against invading pathogens [2, 6]. Once pathogens are recognized, these TLRs trigger a rapid inflammatory response [6]. People with NCGS are found to have higher expressions of TLRs compared to controls, indicating involvement of the innate immune system [6]. Furthermore, imbalances in gut microorganisms (microbiota), which play an important role in regulating cells that protect the intestinal barrier, may also contribute to the onset of NCGS [5].

Summary

From an evolutionary perspective, the rapid increase in gluten related disorders is not surprising as it has not been long since humans began growing and preparing food rather acquiring it through hunting and gathering. Until the agricultural era, humans were not exposed to cereal grains for hundreds of thousands of years. Now, cereal grains like wheat, rice, barley, oats, rye, maize, millet and sorghum are staple foods of mankind around the world. The consequences of mass cereal grain consumption are that humans and our digestive systems have not adapted to develop immunological tolerance to most cereal grain proteins [8]. A repeated number of studies demonstrate the harmful immune responses related to the gluten proteins in wheat. Future posts will examine the gluten free diet (GFD) and its usefulness in combatting gluten-related disorders.

For more information on our services please click here to read more.

References:

1. Brandtzaeg, P. 2007. Why We Develop Food Allergies. American Scientist. January-February. Vol. 95, No. 1, Pg. 28.

2. Czaja-Bulsa, G. 2015. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: A new disease with gluten intolerance. Clinical Nutrition. April. Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 189-194.

3. Carrera-Bastos et al. 2011. The Western Diet and Lifestyle and Diseases of Civilization. Research Reports in Clinical Cardiology. March. Vol. 2. Pp.15-35.

4. Guandalini, S. & Polanco, I. 2015. Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity or Wheat Intolerance Syndrome? The Journal of Pediatrics. April. Vol. 166, No. 4, pp. 805-811.

5. Nylund, L. et al. 2016. The microbiota as a component of the celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Clinical Nutrition Experimental. January. pp. 1-8.

6. Sanz, Y. 2015. Gut microbiota influence the development and function of different host defence mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. Vol. 67, Sup. 2, pp. 28–41.

7. Sapone, A. et al. 2012. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Medicine. February. Vol. 7, pp. 10-13.

8. Scherf, K. A. et al. 2016. Gluten and wheat sensitivities: An overview. Journal of Cereal Science. Vol. 67, pp. 2-11.

9. West, J. et al. 2014. Incidence and prevalence of celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis in the UK over two decades: population-based study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. May. Vol. 109, No. 5, pp. 757-768.

10. White, L. E. et al. 2013. The Rising Incidence of Celiac Disease in Scotland. Paediatrics. October Vol. 132, No. 4, pp. e924-31.

11. Wieser, H. 2007. Chemistry of Gluten Proteins. Food Microbiology. Vol 24, No. 2, pp. 115-119.

12. Wyrick, J. 2013. Gluten Sensitivity: What Does It Really Mean? Scientific American [Online] [Viewed March 03, 2016]. Avialable from: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/gluten-sensitivity-what-does-it-really-mean/.

13. Zuidmeer, L. et al. 2008. The Prevalence of Plant Food Allergies: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. May. Vol. 121, No. 5, pp. 1210-1218.

Did you find this content valuable?

Add yourself to our community to be notified of future content.